Sitting in Rukba’s ice cream parlor. Most of the female customers are wearing head scarves. It is mid-day on Thursday and many people walk by, shopping, getting lunch, going somewhere.

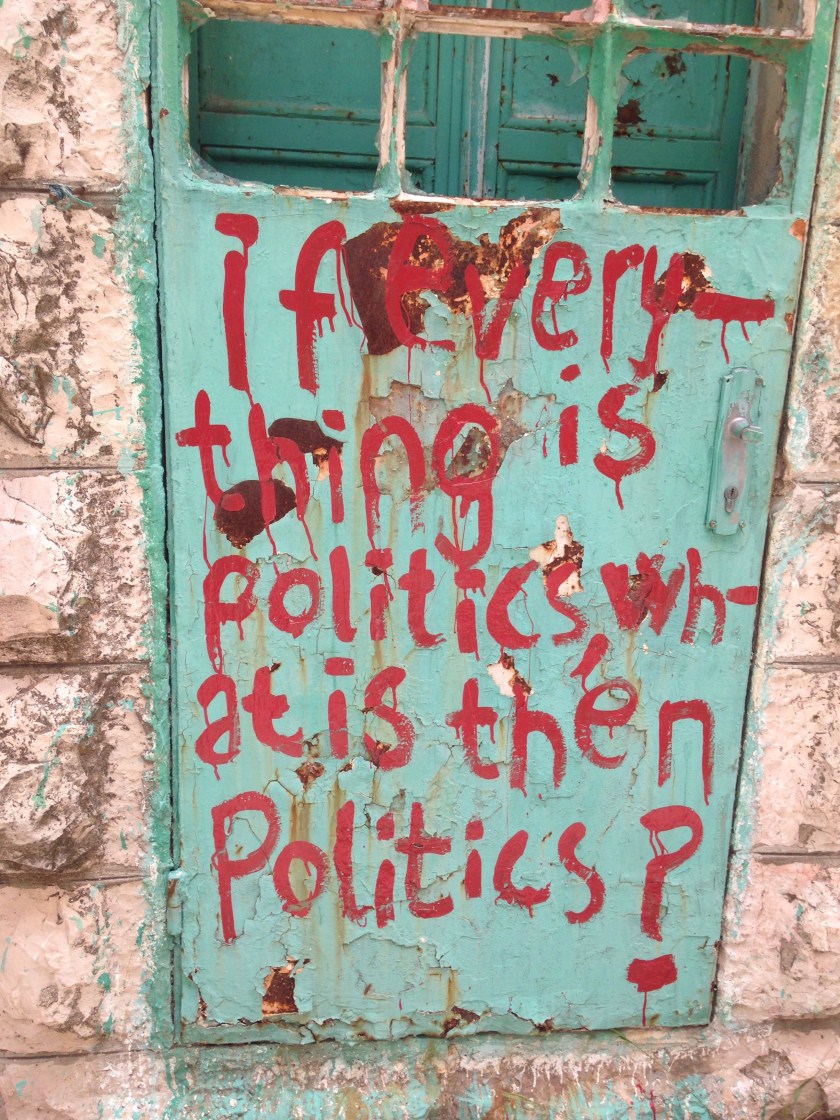

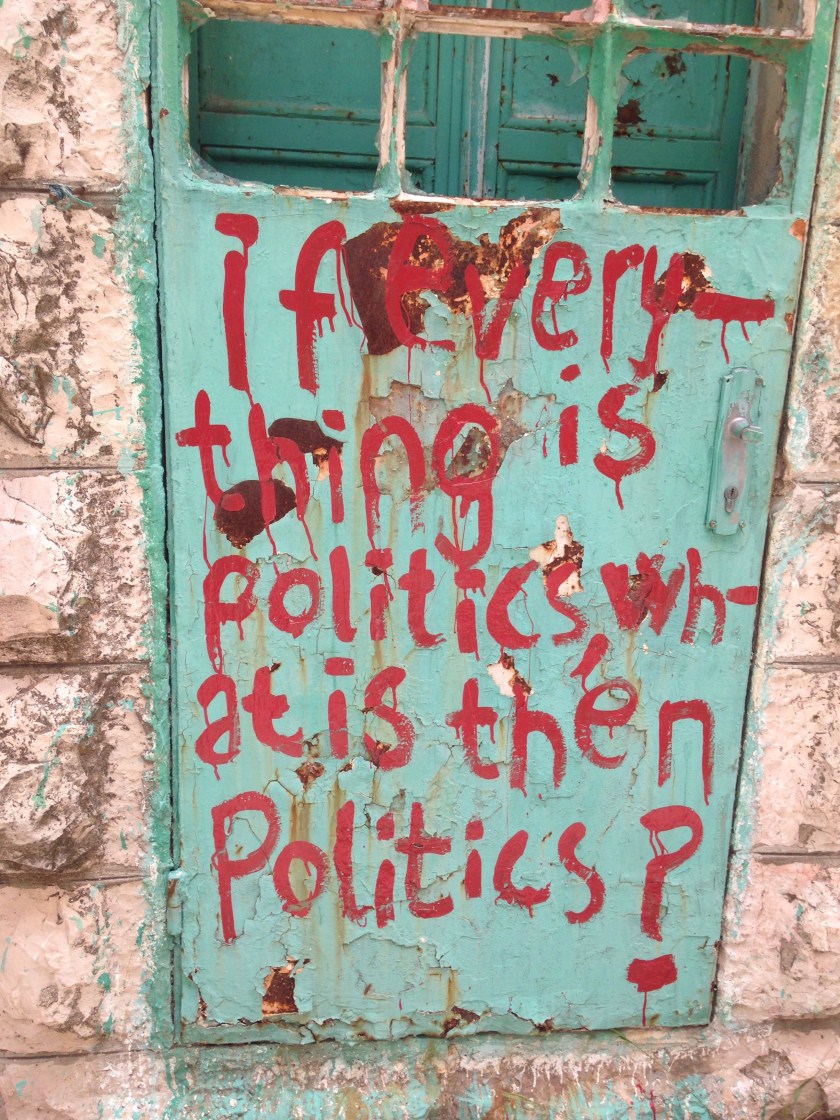

I am in Ramallah, but what do I put as the country? Ramallah, The West Bank? Ramallah, Palestine? Ramallah, The Occupied Territories? Ramallah, Israel? Whichever choice I make has political implications.

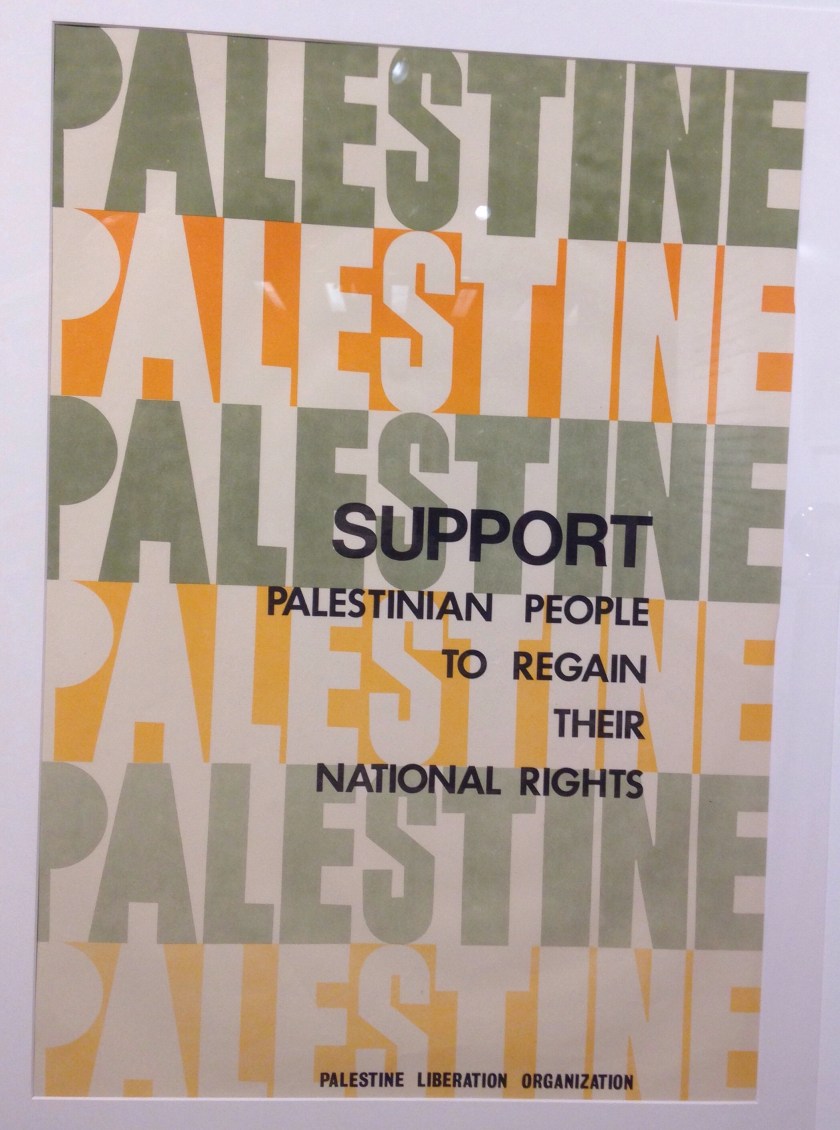

While in Jerusalem, I took a political tour that looked at the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The guide pointed out Jewish Israeli settlements in the Muslim section of the Old City. They were easy to identify, because they fly the Israeli flag prominently. It is illegal to fly the Palestinian flag in Israel, so there are no countervailing visuals.

While in Jerusalem, I took a political tour that looked at the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The guide pointed out Jewish Israeli settlements in the Muslim section of the Old City. They were easy to identify, because they fly the Israeli flag prominently. It is illegal to fly the Palestinian flag in Israel, so there are no countervailing visuals.

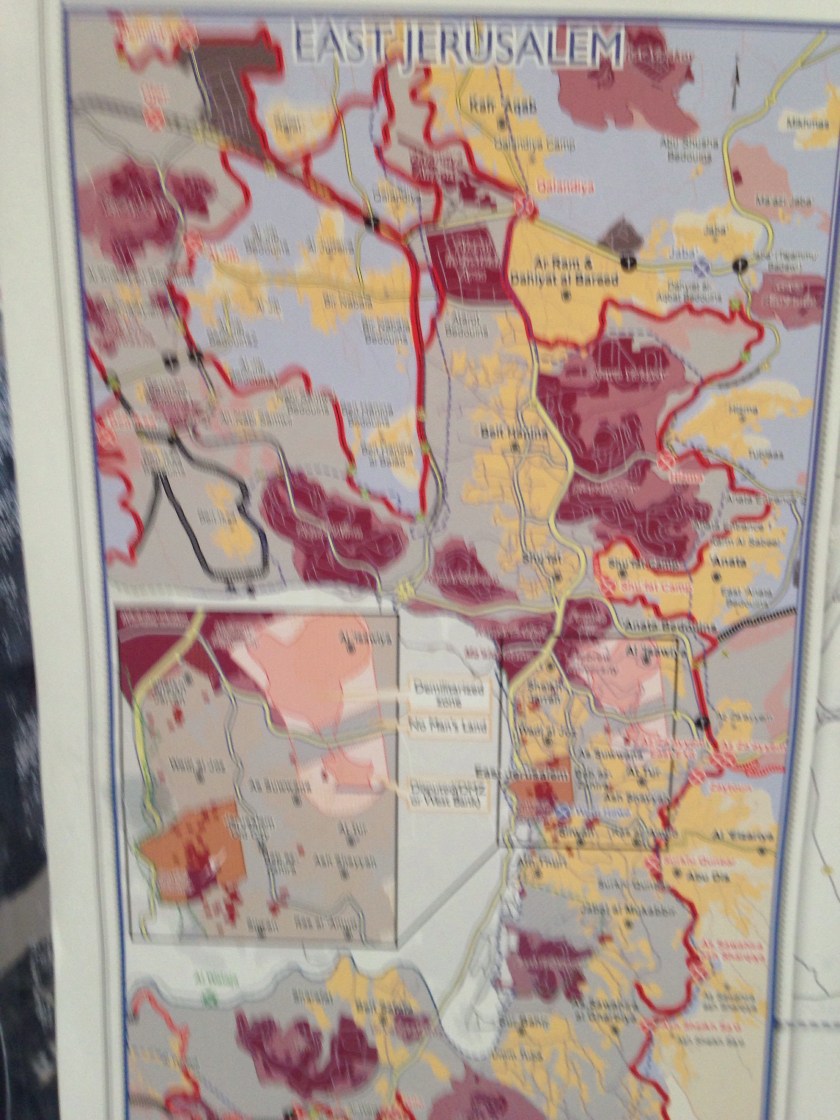

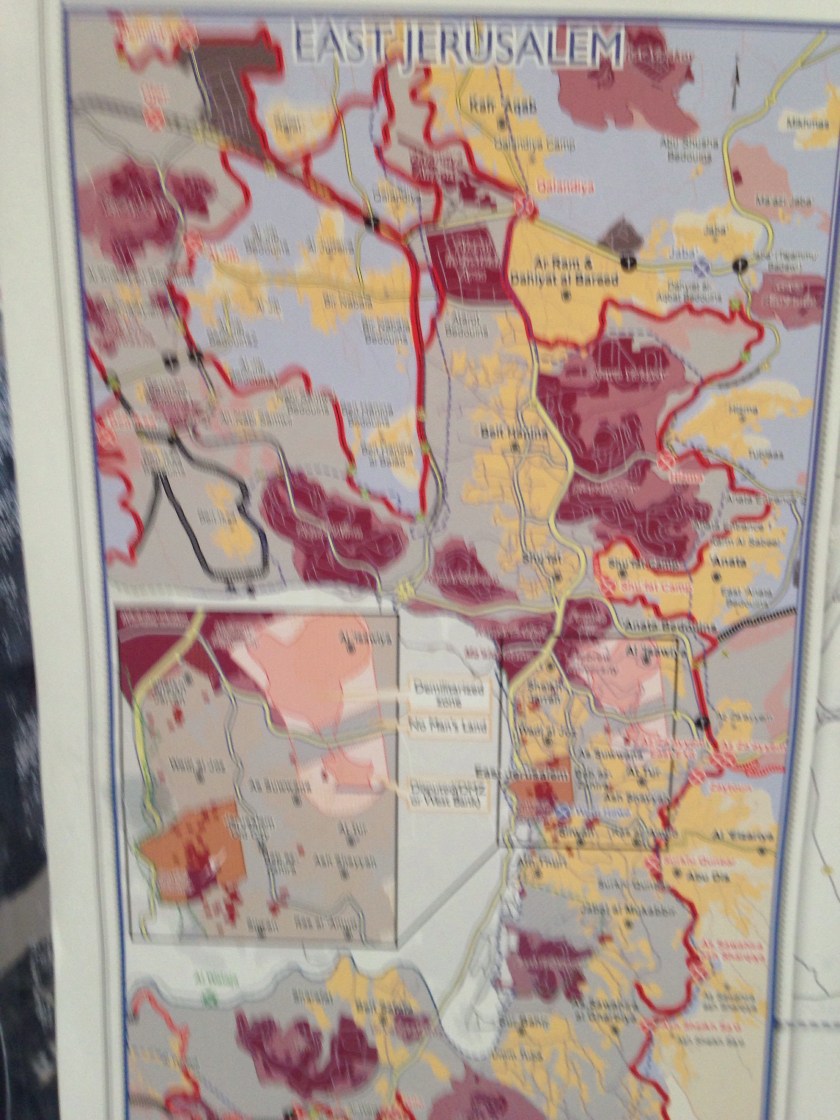

(The Old City of Jerusalem was not part of Israel before the Six Day War in 1967, so it is part of the occupied territories—though a part Israel clearly never wants to relinquish. The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs publishes maps that show the settlements, checkpoints and such in the Occupied Territories. On this map, all of the construction in the Jewish Quarter of the Old City is listed as a Jewish settlement.)

As we wandered around the Muslim section of Old Jerusalem, we ran into a group of eight Israeli men, apparently being trained to usher Jewish settlers to and from their homes in the Muslim section. Outside the Old City, we passed a bus that shuttles settlers to and from their homes in settlements in occupied East Jerusalem. The bus had metal screens over all the windows to try and prevent thrown rocks from breaking them.

As part of the tour, we visited the store at the Western Wall. Inside there are books with acetate overlays of a Jewish Third Temple on the spot where the Dome of the Rock, the third holiest site to Muslims, currently sits. You can also buy puzzles of the Third Temple or t-shirts calling for its construction. Just in the last few days Israel has approved more archeological tunneling under the Dome of the Rock

There are ten new neighborhoods for Jewish Israelis in Jerusalem and none for Palestinians. This means that Palestinians face a severe housing shortage. Palestinians are generally not able to develop new housing even on land they own. The land gets zoned for non-residential uses. We visited one site where Palestinians submitted a plan for a new neighborhood on Palestinian-owned land. The government subsequently announced that the land would become part of a national park .

***

It’s the next day. Late Friday afternoon in Amman. The ruins of the Nymphaeum of the Roman city of Philadelphia are across the street. I am sitting on the shady stoop of a closed shop. Other men sit nearby. The surrounding streets are the central market area of Amman and thick with vendors. Fresh fruits and vegetables. Nuts. Arab sweets. Used clothing from the USA.

It’s the next day. Late Friday afternoon in Amman. The ruins of the Nymphaeum of the Roman city of Philadelphia are across the street. I am sitting on the shady stoop of a closed shop. Other men sit nearby. The surrounding streets are the central market area of Amman and thick with vendors. Fresh fruits and vegetables. Nuts. Arab sweets. Used clothing from the USA. I am relieved to be in Jordan and out of the Occupied Territories. It’s similar to the relief of being in Zambia after spending time in South Africa. To be in a land that is not defined by a conflict between well-to-do European-heritage settlers with the poor indigenous people of color who have largely been pushed off the land. (And yes, Jewish immigrants to Israel are not all European heritage.)

I am relieved to be in Jordan and out of the Occupied Territories. It’s similar to the relief of being in Zambia after spending time in South Africa. To be in a land that is not defined by a conflict between well-to-do European-heritage settlers with the poor indigenous people of color who have largely been pushed off the land. (And yes, Jewish immigrants to Israel are not all European heritage.)

But it’s also more than that. Israel celebrates its independence day on May 14, in three days. That is also the day that the USA is moving its consulate to Jerusalem over Palestinian and many nation’s objections. The next day is Nakba Day, the day Palestinians commemorate the displacement of hundreds of thousands of them from their homes by the Jewish state. Ramadan starts the next day. And two days ago Trump—at Israel’s behest—pulled the USA out of the deal with Iran to limit its nuclear development. Yesterday, Israel launched massive air strikes in Syria attacking Iranian military positions there.

Meanwhile, in the Gaza Ghetto, they are having a March to Return every Friday, demonstrating for their right to return to the homes they lost. 42 Palestinians participating in these marches have already been killed by the Israeli security forces and thousands injured. The protests are climaxing on Nakba day. History is being made.

I took three tours focused on the Palestinian-Israeli conflict: the one in Jerusalem was led by a Jewish Israeli, the ones in Hebron and Qalandiya led by Palestinians. One theme that came up repeatedly was Jewish Israelis trying, successfully in many cases, to get homes from Palestinians by saying to the courts that the house was once owned by Jews. Because Palestinians tend to have less money than Jewish Israelis, they are often challenged to fight these cases in the courts. In Hebron we saw a house decked out in the Israeli flag, where the Israeli courts had recently ruled in favor of the Palestinian—but so recently they hadn’t had the chance to reclaim the property and remove the Israeli flags.

You may have already noticed the irony of Israelis saying they have the right to reclaim a house that was once owned by Jews over a hundred years ago, but Palestinians do not have the right to return to their home—or even to the area—where they once lived.

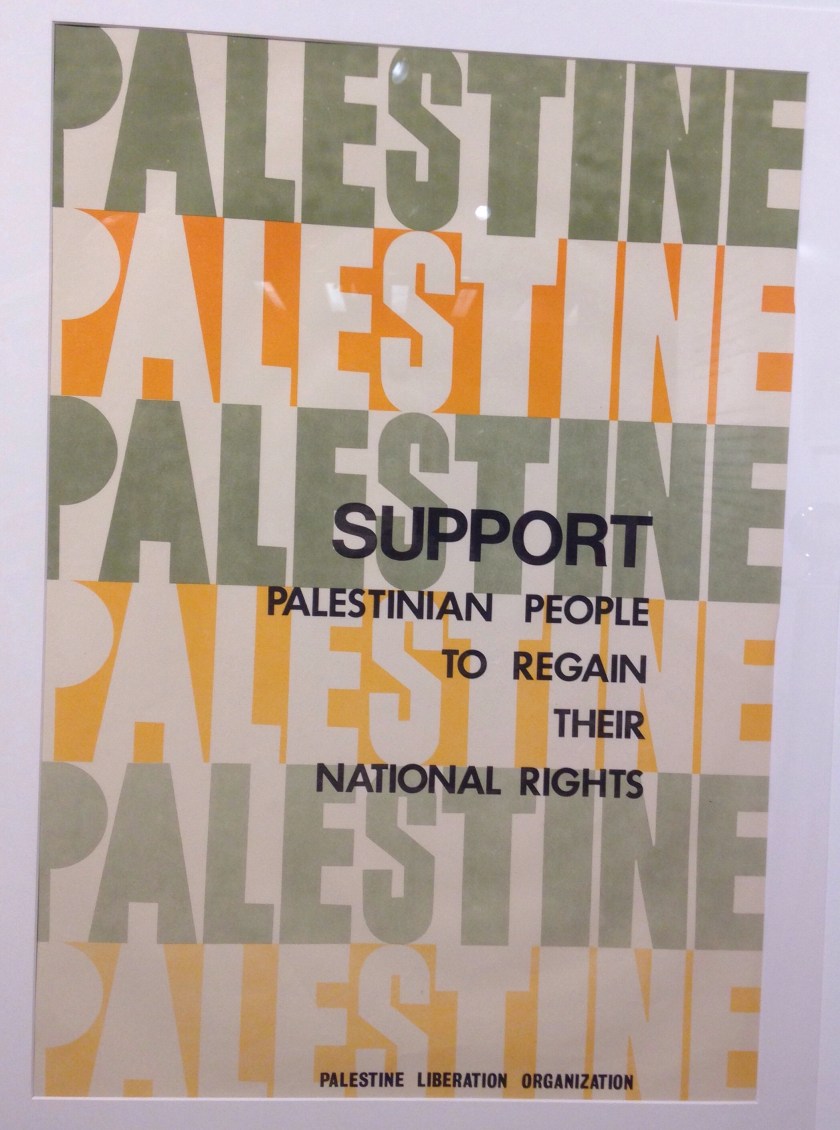

Walking back to my hostel after visiting the Israel Museum, I came upon a bus full of American teenagers walking down the sidewalk. They were all wearing the same orange lanyard. I looked and the organization name on the lanyard was ‘Birthright Israel.’ If you’re a Jew living anywhere in the world, you have a ‘birthright’ to live in the land of Israel. But the Palestinians who were displaced from this land–or still live here–do not have these same rights.

Yesterday evening when I left the Area D hostel to find dinner, I ran into a right of return event on the corner. There was a group of young people from some scouting organization standing in lines. A few young people in front held flags and most played the drums. I didn’t stay for the speeches, which were in Arabic. There was no intense political atmosphere around the event. It seemed a family event. The scouting leaders and mothers were wandering about taking pictures.

The essential information is communicated by flags two girls were holding. At the top is the Palestinian flag, which is the same as the flag of the Great Arab Revolt of 1917. (Jordan’s flag is identical, except with a star added.) Below the Palestinian flag is the outline of Palestine and a key and the word ‘Return’ in English and Arabic.

The essential information is communicated by flags two girls were holding. At the top is the Palestinian flag, which is the same as the flag of the Great Arab Revolt of 1917. (Jordan’s flag is identical, except with a star added.) Below the Palestinian flag is the outline of Palestine and a key and the word ‘Return’ in English and Arabic.

The key has become a symbol for the return movement. When Palestinians fled or were forced to flee their homes during the war in 1948, they assumed that they would be able to return when the fighting stopped. Only the Israelis wouldn’t allow them to return (in violation of international law). So now all they left is the key.

***

Now I’m sitting on the rooftop garden of my hotel in Amman. It is almost directly across the street from the well-preserved amphitheater of the Roman city of Philadelphia. There is a big square in front of the amphitheater. Hundreds of Jordanians are out, chatting with friends, kicking a ball, dancing.

Now I’m sitting on the rooftop garden of my hotel in Amman. It is almost directly across the street from the well-preserved amphitheater of the Roman city of Philadelphia. There is a big square in front of the amphitheater. Hundreds of Jordanians are out, chatting with friends, kicking a ball, dancing.

Both of my Palestinian guides had close friends or relatives killed by the Israeli security forces. Abud lost an uncle and two cousins. His uncle’s house was broken into at night by the IDF and he was killed in his bed. Then they looked at his ID and realized they had killed the wrong person. The Israeli soldier was jailed for a week, but then released. “Mistakes happen.” Mohammad and his friend were university students going through a checkpoint. He said they were sitting down doing nothing when an Israeli guard ‘lost it’ and shot his friend in the neck, killing him.

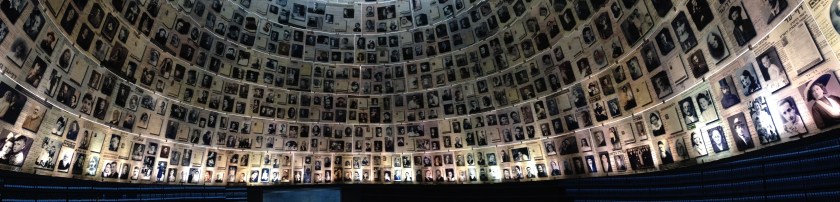

On the visit to Hebron, one of the largest cities in the West Bank, we visited the center of the city and the old market. The area is now deserted, closed by the Israeli military since the second Intifada. There are 800 Israeli settlers living in the heart of Hebron, the Israeli government won’t make them leave, and so huge sections of historic Hebron are abandoned. It was interesting to listen to Abud talk about old Hebron and express his longing for the city of his youth. It reminded me of the reminisces of Jews talking about the homes they lost in the Holocaust.

On the visit to Hebron, one of the largest cities in the West Bank, we visited the center of the city and the old market. The area is now deserted, closed by the Israeli military since the second Intifada. There are 800 Israeli settlers living in the heart of Hebron, the Israeli government won’t make them leave, and so huge sections of historic Hebron are abandoned. It was interesting to listen to Abud talk about old Hebron and express his longing for the city of his youth. It reminded me of the reminisces of Jews talking about the homes they lost in the Holocaust.

About 2,500 members of the Israeli security forces protect the 800 Jewish Israelis living in Hebron. Israeli settlers are allowed to carry guns. It felt very strange to be walking through the Jewish neighborhood and have a man walk within feet of me in t-shirt and gym shorts carrying a submachine gun.

About 2,500 members of the Israeli security forces protect the 800 Jewish Israelis living in Hebron. Israeli settlers are allowed to carry guns. It felt very strange to be walking through the Jewish neighborhood and have a man walk within feet of me in t-shirt and gym shorts carrying a submachine gun.

A couple of minutes later, a bus pulled up and a stream of Israeli soldiers got off. They were apparently returning form the big settlement on the outskirts of Hebron where the Jewish Israelis shop. Almost everyone on the bus was a solder carrying a sub-machine gun, along with their shopping bags.

A couple of minutes later, a bus pulled up and a stream of Israeli soldiers got off. They were apparently returning form the big settlement on the outskirts of Hebron where the Jewish Israelis shop. Almost everyone on the bus was a solder carrying a sub-machine gun, along with their shopping bags.

The Israeli government does have a plaque giving an explanation. The plaque acknowledges that the military forced the businesses in the central business district to close, but says it was forced by the terrorist activities of the second Intifada. The plaque implies that it’s not a big deal that the market is closed, saying that are other bustling business districts nearby that the Palestinians can use. I think this gets to the heart of the Israeli’s viewpoint in general. “There are other Arab countries nearby. Why don’t the Palestinians just move there and leave this land to us?”

The poor treatment of Palestinians is not accidental or an error. It must be official policy. If we treat them poorly enough, hopefully eventually they’ll move on. And Israel certainly doesn’t want the Palestinian refugees in other nearby countries, like Jordan, to return to Palestine because conditions for Palestinians had improved so much.

The poor treatment of Palestinians is not accidental or an error. It must be official policy. If we treat them poorly enough, hopefully eventually they’ll move on. And Israel certainly doesn’t want the Palestinian refugees in other nearby countries, like Jordan, to return to Palestine because conditions for Palestinians had improved so much.

What seems interesting to me is that most Jews moved away from the land of Israel in 70 CE. While some Jews have always lived here, it was a small percentage of the population and the area was never under Jewish control from 70 until 1948. The area was under Muslim control from about 680 to 1948—except for about 90 years of Crusader control in the 1200s. Yet the Jews maintained such a deep connection to the land that now, 2,000 years later, they have reclaimed it as a national home. Why is it so difficult for people who nurtured a 2,000 year love for a land to understand the love of the land by another people who were forced off it in the last generation or two and who still live nearby?

I am catching a flight at noon tomorrow from Amman to London. It took me over six hours today to travel from Ramallah to Amman, which is a distance of only 69 kilometers or 43 miles. Because today is a Friday, the border with Jordan closes at 1:30 pm. I left the hostel before 7:00 am to catch a bus to Jerusalem. The bus station, actually the open parking lot where the buses park, is across the street from my hostel. When I arrived mid-afternoon a few days ago, the lot was jammed. This morning, it was completely empty. Eventually one small bus arrived and waited for passengers. It wasn’t the number for the bus to Jerusalem and so I kept waiting. Eventually I went over and asked if that bus was going to Jerusalem. They said that there was no through bus to Jerusalem today. I would need to take this bus to the Qalandiya checkpoint, walk through the checkpoint, and then pick up a bus to Jerusalem on the other side. We sat for a while waiting for more people to fill the bus and eventually headed off for Qalandiya.

I am catching a flight at noon tomorrow from Amman to London. It took me over six hours today to travel from Ramallah to Amman, which is a distance of only 69 kilometers or 43 miles. Because today is a Friday, the border with Jordan closes at 1:30 pm. I left the hostel before 7:00 am to catch a bus to Jerusalem. The bus station, actually the open parking lot where the buses park, is across the street from my hostel. When I arrived mid-afternoon a few days ago, the lot was jammed. This morning, it was completely empty. Eventually one small bus arrived and waited for passengers. It wasn’t the number for the bus to Jerusalem and so I kept waiting. Eventually I went over and asked if that bus was going to Jerusalem. They said that there was no through bus to Jerusalem today. I would need to take this bus to the Qalandiya checkpoint, walk through the checkpoint, and then pick up a bus to Jerusalem on the other side. We sat for a while waiting for more people to fill the bus and eventually headed off for Qalandiya.

Usually ‘internationals,’ as the Palestinians called us, get different treatment than the locals, particularly with regard to freedom of movement. For example, on a through bus to Jerusalem an international would generally get to stay on the bus and the member of the Israeli security forces would come on board to check their ID. The Palestinians exit the bus and go through the checkpoint.

On this occasion, I was there with the locals. All of the signs were in Arabic and so I joined the crowd of over 100 people lined up trying to get through the first set of tall metal turnstiles. The tunstiles were usually locked and the Palestinians were waiting for the tunstile for their line to unlock and a few to squeeze through.

Standing in line I talked with a Palestinian man who works in Jerusalem. He bemoaned the hour plus each day he spends going through the checkpoint to get to his job. ‘I have no problem with Jews. They are wonderful people and I have many Jewish friends. It’s the Israeli government I have a problem with. And I have problems with Arab governments too.’

After about 20 minutes, I managed to squeeze myself, my suitcase, backpack and halvah through the first gate. Having gotten through the first gate, we went through three sets of metal cages before you were finally out on the other side. We were now in another section with lines before four other gates. I choose gate 1, which was the shortest line. But after standing there for 10-15 minutes, we realized our line hadn’t moved at all and others had. I headed off to another line.

After about 20 minutes, I managed to squeeze myself, my suitcase, backpack and halvah through the first gate. Having gotten through the first gate, we went through three sets of metal cages before you were finally out on the other side. We were now in another section with lines before four other gates. I choose gate 1, which was the shortest line. But after standing there for 10-15 minutes, we realized our line hadn’t moved at all and others had. I headed off to another line.

As I stood between the first turnstile and the second, they would unlock the second turnstile long enough for a few people to go though and then lock it again. On the other side of this was an airport style metal detector for bags and the member of the IDF who checked IDs.

I was behind a large group of Palestinian women. They weren’t good at taking turns. When the gate was unlocked, two would always try to squeeze through. Instead of the turnstile turning, they would argue and get stuck.

When the group of women had all passed through, I finally got into the fourth area where your ID was checked. I don’t even think the Israeli security guard even glanced at my ID. He looked at me and with a little wave of his hands indicated that I could go through.

It took me 75 minutes to get through the checkpoint and over six hours to travel the 69 kilometers/42 miles from Ramallah to Amman. Antler reason to be relieved to be in Amman.

Going through the checkpoint felt debilitating to me, like we were some kind of animal. I got a little claustrophobic. The only Israeli we saw that whole time was the one moment when we showed someone our ID through the bullet-proof glass. Otherwise it was hundreds of unhappy Palestinians waiting, pushing, shouting, trying to get to work or a doctor’s appointment or, in my case, a bus to the King Hussein Bridge.

No one I talked with had a solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, but I think part of the solution will need to be pressure from the outside on Israel. It’s clear that in the case of South Africa, pressure from outside the country played a key role in getting whites to the bargaining table and willing to allow full legal rights for all South Africans. The Israeli-Palestinian situation is not identical, of course. One of the biggest difference is the need to be clearly opposed to the oppression of Jews while also pushing for freedom and equality for Palestinians.

Two years ago I was at an international conference at King’s Academy. One of the King’s Academy students was a Palestinian whose grandfather has the key to their house in what is now Israel. One dinner our group had an hour long conversation about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. One thing the Palestinian girl said was: “I understand that Jews need a safe place to liv, but why did they have to take our homes?”

I visited the Qalandiya refugee camp with a Palestinian guide and one other man. Matthew from Britain. In my almost four months traveling I have yet to experience anyone saying anything negative about the United States. I tried to apologize for Trump to Mohammad and he said it wasn’t necessary. Matthew, however, reported that he had experienced several instances of Palestinians reacting negatively when he told Palestinians he was from the UK. It’s because of the Balfour Declaration and several of them specifically referenced this to him. The declaration reads: His Majesty’s government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.

I visited the Qalandiya refugee camp with a Palestinian guide and one other man. Matthew from Britain. In my almost four months traveling I have yet to experience anyone saying anything negative about the United States. I tried to apologize for Trump to Mohammad and he said it wasn’t necessary. Matthew, however, reported that he had experienced several instances of Palestinians reacting negatively when he told Palestinians he was from the UK. It’s because of the Balfour Declaration and several of them specifically referenced this to him. The declaration reads: His Majesty’s government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.

Many Palestinians blame Britain for the lose of their land and homes, but no one seems to remember or act on the part about the rights of non-Jewish communities.

This long blog posting will just end without a neat turn of phrase or summation, which seems fitting.

The Athenian School’s first required meeting for faculty is next Thursday. The long sweep of my sabbatical and summer break is about to be broken. Now I am in a redwood forest at Bullfrog Pond campground, 90 miles north of San Francisco. A one-lane road heads from the 2,000-year-old trees on the valley floor up to the ridge and campground. As I drove here yesterday, I wondered how I would escape should a fire hit. I imagined myself in the middle of the pond, breathing through a straw, the surrounding woods aflame.

The Athenian School’s first required meeting for faculty is next Thursday. The long sweep of my sabbatical and summer break is about to be broken. Now I am in a redwood forest at Bullfrog Pond campground, 90 miles north of San Francisco. A one-lane road heads from the 2,000-year-old trees on the valley floor up to the ridge and campground. As I drove here yesterday, I wondered how I would escape should a fire hit. I imagined myself in the middle of the pond, breathing through a straw, the surrounding woods aflame. The camping trips were partly an opportunity for Kaia to take on challenges. The first years, the challenges were physical. She would scamper up downed redwood trees and walk along the spine of these fallen giants. Then the challenges became social, as she wanted to make friends with other children staying at the campground.

The camping trips were partly an opportunity for Kaia to take on challenges. The first years, the challenges were physical. She would scamper up downed redwood trees and walk along the spine of these fallen giants. Then the challenges became social, as she wanted to make friends with other children staying at the campground. There is no threat of rain, so I didn’t put the fly on my tent. The entire top of the tent is mesh and I can lie on my sleeping pad and look at the trees and sky. When I woke this morning, the sky was not blue. The winds have shifted and the grey smoke from the fires is now overhead. A faint sun strains to reach the earth. It is a bit like the light of a solar eclipse, but with a grey sky and an acrid smell.

There is no threat of rain, so I didn’t put the fly on my tent. The entire top of the tent is mesh and I can lie on my sleeping pad and look at the trees and sky. When I woke this morning, the sky was not blue. The winds have shifted and the grey smoke from the fires is now overhead. A faint sun strains to reach the earth. It is a bit like the light of a solar eclipse, but with a grey sky and an acrid smell. For the ancient Greeks, death was the thing. Their gods are just like us, but they are immortal. The only way humans could achieve immortality was by being remembered for heroic deeds. The Greek plays and literature usually were about life and death. Patroclus, Hector and Achilles. Agamemnon, Hecuba and Medea. Our species has made a mess of this beautiful planet. Would outsiders call the drama of humanity a tragedy?

For the ancient Greeks, death was the thing. Their gods are just like us, but they are immortal. The only way humans could achieve immortality was by being remembered for heroic deeds. The Greek plays and literature usually were about life and death. Patroclus, Hector and Achilles. Agamemnon, Hecuba and Medea. Our species has made a mess of this beautiful planet. Would outsiders call the drama of humanity a tragedy?

London. I awoke this morning to the sound of the bells at St. Paul’s Cathedral. There is a hostel in the building that once housed the boys’ choir of St. Paul’s. I love staying here because it is a couple of blocks from the Millennium Bridge and the Thames. I walk out on the bridge last thing before going to bed every night and then again first thing every morning.

London. I awoke this morning to the sound of the bells at St. Paul’s Cathedral. There is a hostel in the building that once housed the boys’ choir of St. Paul’s. I love staying here because it is a couple of blocks from the Millennium Bridge and the Thames. I walk out on the bridge last thing before going to bed every night and then again first thing every morning. I often begin my blog postings with a description of where I am at that moment. And the most remarkable thing about my trip is the string of ‘I am heres.’ It has been incredible. Johannesburg. Vryburg. Haertzenburg. The Iron Crown. Sandton. Lusaka. Bauleni. Nelspruit. White River. Zwelisha Township. Masoyi Township. Karongwe Game Reserve. Selati Game Reserve. Soweto. Royal Natal National Park. Mtamta. Coffee Bay. Lubanzi. Bulungula. Jeffrey’s Bay. Wilderness. Cape Town. Cape of Good Hope. West Coast National Park. Cederberg Wilderness Area. Franschhoek. Lion’s Head. London. Amman. Petra. Wadi Rum. Aqaba. The Red Sea. Jerusalem. Ramallah. Hebron. Qalandiya. Bath.

I often begin my blog postings with a description of where I am at that moment. And the most remarkable thing about my trip is the string of ‘I am heres.’ It has been incredible. Johannesburg. Vryburg. Haertzenburg. The Iron Crown. Sandton. Lusaka. Bauleni. Nelspruit. White River. Zwelisha Township. Masoyi Township. Karongwe Game Reserve. Selati Game Reserve. Soweto. Royal Natal National Park. Mtamta. Coffee Bay. Lubanzi. Bulungula. Jeffrey’s Bay. Wilderness. Cape Town. Cape of Good Hope. West Coast National Park. Cederberg Wilderness Area. Franschhoek. Lion’s Head. London. Amman. Petra. Wadi Rum. Aqaba. The Red Sea. Jerusalem. Ramallah. Hebron. Qalandiya. Bath. Now I’m on a train to Felsted, northeast of London, my last stop before flying home tomorrow. I am looking forward to seeing my family and friends back in California, to enjoying the many pleasures of where I live–the amazing food, incredible natural beauty and great art. But the truth is I would happily keep going. Leave London tomorrow for, say, India to visit friends and schools and help with some community projects.

Now I’m on a train to Felsted, northeast of London, my last stop before flying home tomorrow. I am looking forward to seeing my family and friends back in California, to enjoying the many pleasures of where I live–the amazing food, incredible natural beauty and great art. But the truth is I would happily keep going. Leave London tomorrow for, say, India to visit friends and schools and help with some community projects. I return to California in time for the start of my summer vacation, so the transition shouldn’t be too painful. My sabbatical doesn’t end when I land in San Francisco, just the being-out-of-the-USA part. But I can’t help but think about my life when I’m back at work and going about my daily rituals. I have a great job running the community service and international programs at the Athenian School, but it’s not as exciting as this trip. My brain gets stuffed with thinking about the myriad details of the many work projects I’m jugging. I get caught up in the culture of work and busyness. Maybe I’ll be able to shift that some. Maybe not.

I return to California in time for the start of my summer vacation, so the transition shouldn’t be too painful. My sabbatical doesn’t end when I land in San Francisco, just the being-out-of-the-USA part. But I can’t help but think about my life when I’m back at work and going about my daily rituals. I have a great job running the community service and international programs at the Athenian School, but it’s not as exciting as this trip. My brain gets stuffed with thinking about the myriad details of the many work projects I’m jugging. I get caught up in the culture of work and busyness. Maybe I’ll be able to shift that some. Maybe not.

While in Jerusalem, I took a political tour that looked at the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The guide pointed out Jewish Israeli settlements in the Muslim section of the Old City. They were easy to identify, because they fly the Israeli flag prominently. It is illegal to fly the Palestinian flag in Israel, so there are no countervailing visuals.

While in Jerusalem, I took a political tour that looked at the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The guide pointed out Jewish Israeli settlements in the Muslim section of the Old City. They were easy to identify, because they fly the Israeli flag prominently. It is illegal to fly the Palestinian flag in Israel, so there are no countervailing visuals. It’s the next day. Late Friday afternoon in Amman. The ruins of the Nymphaeum of the Roman city of Philadelphia are across the street. I am sitting on the shady stoop of a closed shop. Other men sit nearby. The surrounding streets are the central market area of Amman and thick with vendors. Fresh fruits and vegetables. Nuts. Arab sweets. Used clothing from the USA.

It’s the next day. Late Friday afternoon in Amman. The ruins of the Nymphaeum of the Roman city of Philadelphia are across the street. I am sitting on the shady stoop of a closed shop. Other men sit nearby. The surrounding streets are the central market area of Amman and thick with vendors. Fresh fruits and vegetables. Nuts. Arab sweets. Used clothing from the USA. I am relieved to be in Jordan and out of the Occupied Territories. It’s similar to the relief of being in Zambia after spending time in South Africa. To be in a land that is not defined by a conflict between well-to-do European-heritage settlers with the poor indigenous people of color who have largely been pushed off the land. (And yes, Jewish immigrants to Israel are not all European heritage.)

I am relieved to be in Jordan and out of the Occupied Territories. It’s similar to the relief of being in Zambia after spending time in South Africa. To be in a land that is not defined by a conflict between well-to-do European-heritage settlers with the poor indigenous people of color who have largely been pushed off the land. (And yes, Jewish immigrants to Israel are not all European heritage.) The essential information is communicated by flags two girls were holding. At the top is the Palestinian flag, which is the same as the flag of the Great Arab Revolt of 1917. (Jordan’s flag is identical, except with a star added.) Below the Palestinian flag is the outline of Palestine and a key and the word ‘Return’ in English and Arabic.

The essential information is communicated by flags two girls were holding. At the top is the Palestinian flag, which is the same as the flag of the Great Arab Revolt of 1917. (Jordan’s flag is identical, except with a star added.) Below the Palestinian flag is the outline of Palestine and a key and the word ‘Return’ in English and Arabic. Now I’m sitting on the rooftop garden of my hotel in Amman. It is almost directly across the street from the well-preserved amphitheater of the Roman city of Philadelphia. There is a big square in front of the amphitheater. Hundreds of Jordanians are out, chatting with friends, kicking a ball, dancing.

Now I’m sitting on the rooftop garden of my hotel in Amman. It is almost directly across the street from the well-preserved amphitheater of the Roman city of Philadelphia. There is a big square in front of the amphitheater. Hundreds of Jordanians are out, chatting with friends, kicking a ball, dancing. On the visit to Hebron, one of the largest cities in the West Bank, we visited the center of the city and the old market. The area is now deserted, closed by the Israeli military since the second Intifada. There are 800 Israeli settlers living in the heart of Hebron, the Israeli government won’t make them leave, and so huge sections of historic Hebron are abandoned. It was interesting to listen to Abud talk about old Hebron and express his longing for the city of his youth. It reminded me of the reminisces of Jews talking about the homes they lost in the Holocaust.

On the visit to Hebron, one of the largest cities in the West Bank, we visited the center of the city and the old market. The area is now deserted, closed by the Israeli military since the second Intifada. There are 800 Israeli settlers living in the heart of Hebron, the Israeli government won’t make them leave, and so huge sections of historic Hebron are abandoned. It was interesting to listen to Abud talk about old Hebron and express his longing for the city of his youth. It reminded me of the reminisces of Jews talking about the homes they lost in the Holocaust. About 2,500 members of the Israeli security forces protect the 800 Jewish Israelis living in Hebron. Israeli settlers are allowed to carry guns. It felt very strange to be walking through the Jewish neighborhood and have a man walk within feet of me in t-shirt and gym shorts carrying a submachine gun.

About 2,500 members of the Israeli security forces protect the 800 Jewish Israelis living in Hebron. Israeli settlers are allowed to carry guns. It felt very strange to be walking through the Jewish neighborhood and have a man walk within feet of me in t-shirt and gym shorts carrying a submachine gun. A couple of minutes later, a bus pulled up and a stream of Israeli soldiers got off. They were apparently returning form the big settlement on the outskirts of Hebron where the Jewish Israelis shop. Almost everyone on the bus was a solder carrying a sub-machine gun, along with their shopping bags.

A couple of minutes later, a bus pulled up and a stream of Israeli soldiers got off. They were apparently returning form the big settlement on the outskirts of Hebron where the Jewish Israelis shop. Almost everyone on the bus was a solder carrying a sub-machine gun, along with their shopping bags. The poor treatment of Palestinians is not accidental or an error. It must be official policy. If we treat them poorly enough, hopefully eventually they’ll move on. And Israel certainly doesn’t want the Palestinian refugees in other nearby countries, like Jordan, to return to Palestine because conditions for Palestinians had improved so much.

The poor treatment of Palestinians is not accidental or an error. It must be official policy. If we treat them poorly enough, hopefully eventually they’ll move on. And Israel certainly doesn’t want the Palestinian refugees in other nearby countries, like Jordan, to return to Palestine because conditions for Palestinians had improved so much. I am catching a flight at noon tomorrow from Amman to London. It took me over six hours today to travel from Ramallah to Amman, which is a distance of only 69 kilometers or 43 miles. Because today is a Friday, the border with Jordan closes at 1:30 pm. I left the hostel before 7:00 am to catch a bus to Jerusalem. The bus station, actually the open parking lot where the buses park, is across the street from my hostel. When I arrived mid-afternoon a few days ago, the lot was jammed. This morning, it was completely empty. Eventually one small bus arrived and waited for passengers. It wasn’t the number for the bus to Jerusalem and so I kept waiting. Eventually I went over and asked if that bus was going to Jerusalem. They said that there was no through bus to Jerusalem today. I would need to take this bus to the Qalandiya checkpoint, walk through the checkpoint, and then pick up a bus to Jerusalem on the other side. We sat for a while waiting for more people to fill the bus and eventually headed off for Qalandiya.

I am catching a flight at noon tomorrow from Amman to London. It took me over six hours today to travel from Ramallah to Amman, which is a distance of only 69 kilometers or 43 miles. Because today is a Friday, the border with Jordan closes at 1:30 pm. I left the hostel before 7:00 am to catch a bus to Jerusalem. The bus station, actually the open parking lot where the buses park, is across the street from my hostel. When I arrived mid-afternoon a few days ago, the lot was jammed. This morning, it was completely empty. Eventually one small bus arrived and waited for passengers. It wasn’t the number for the bus to Jerusalem and so I kept waiting. Eventually I went over and asked if that bus was going to Jerusalem. They said that there was no through bus to Jerusalem today. I would need to take this bus to the Qalandiya checkpoint, walk through the checkpoint, and then pick up a bus to Jerusalem on the other side. We sat for a while waiting for more people to fill the bus and eventually headed off for Qalandiya. After about 20 minutes, I managed to squeeze myself, my suitcase, backpack and halvah through the first gate. Having gotten through the first gate, we went through three sets of metal cages before you were finally out on the other side. We were now in another section with lines before four other gates. I choose gate 1, which was the shortest line. But after standing there for 10-15 minutes, we realized our line hadn’t moved at all and others had. I headed off to another line.

After about 20 minutes, I managed to squeeze myself, my suitcase, backpack and halvah through the first gate. Having gotten through the first gate, we went through three sets of metal cages before you were finally out on the other side. We were now in another section with lines before four other gates. I choose gate 1, which was the shortest line. But after standing there for 10-15 minutes, we realized our line hadn’t moved at all and others had. I headed off to another line. I visited the Qalandiya refugee camp with a Palestinian guide and one other man. Matthew from Britain. In my almost four months traveling I have yet to experience anyone saying anything negative about the United States. I tried to apologize for Trump to Mohammad and he said it wasn’t necessary. Matthew, however, reported that he had experienced several instances of Palestinians reacting negatively when he told Palestinians he was from the UK. It’s because of the Balfour Declaration and several of them specifically referenced this to him. The declaration reads: His Majesty’s government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.

I visited the Qalandiya refugee camp with a Palestinian guide and one other man. Matthew from Britain. In my almost four months traveling I have yet to experience anyone saying anything negative about the United States. I tried to apologize for Trump to Mohammad and he said it wasn’t necessary. Matthew, however, reported that he had experienced several instances of Palestinians reacting negatively when he told Palestinians he was from the UK. It’s because of the Balfour Declaration and several of them specifically referenced this to him. The declaration reads: His Majesty’s government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.

I spent the next two days wandering Jerusalem. Waling through the narrow streets of the Old City, hiking the ramparts, visiting the Church of the Holy Sepulcher and Mount of Olives. Most of my time was spent in the Old City. The Christian pilgrims were very visible, but it was clear that the residents were mostly Jewish or Muslim.

I spent the next two days wandering Jerusalem. Waling through the narrow streets of the Old City, hiking the ramparts, visiting the Church of the Holy Sepulcher and Mount of Olives. Most of my time was spent in the Old City. The Christian pilgrims were very visible, but it was clear that the residents were mostly Jewish or Muslim.

Jewish women get into the act too. Married orthodox women are supposed to cover their hair. Wearing a wig fulfills this requirement, so wearing wigs is big here among Jewish women.

Jewish women get into the act too. Married orthodox women are supposed to cover their hair. Wearing a wig fulfills this requirement, so wearing wigs is big here among Jewish women. I enjoyed watching a Jewish family play tag or Jewish boys do hip hop dancing on a sidewalk, seeing Jewish men ride their children on a bike or Jewish women chat with each other. I saw Jewish men sitting around reading the Bible—or even reading while they walked.

I enjoyed watching a Jewish family play tag or Jewish boys do hip hop dancing on a sidewalk, seeing Jewish men ride their children on a bike or Jewish women chat with each other. I saw Jewish men sitting around reading the Bible—or even reading while they walked.

In my wanderings, the security forces seem to be primarily in the Muslim section of the city, which makes them feel a bit like an occupying army. There are two main gates to the Old City that people use: Damascus and Jaffa. Damascus is the main gate that Muslims use. It has three Israeli security stations at the gate. Jewish Israelis would generally not use Damascus Gate and would use Jaffa, the next gate over around the corner. No visible security presence there.

In my wanderings, the security forces seem to be primarily in the Muslim section of the city, which makes them feel a bit like an occupying army. There are two main gates to the Old City that people use: Damascus and Jaffa. Damascus is the main gate that Muslims use. It has three Israeli security stations at the gate. Jewish Israelis would generally not use Damascus Gate and would use Jaffa, the next gate over around the corner. No visible security presence there.

I hung out at Al-Aqsa for several hours. I walked around the Dome of the Rock three times, enjoying its architecture and glittering gold top. Most Muslim streets in the Old City lead to Al-Aqsa. There are eight gates to Al-Aqsa with guards at each. Muslims are allowed in, but others are turned away. Just the day before I had stood on the other side of the Cotton Merchants gate unable to cross though.

I hung out at Al-Aqsa for several hours. I walked around the Dome of the Rock three times, enjoying its architecture and glittering gold top. Most Muslim streets in the Old City lead to Al-Aqsa. There are eight gates to Al-Aqsa with guards at each. Muslims are allowed in, but others are turned away. Just the day before I had stood on the other side of the Cotton Merchants gate unable to cross though.

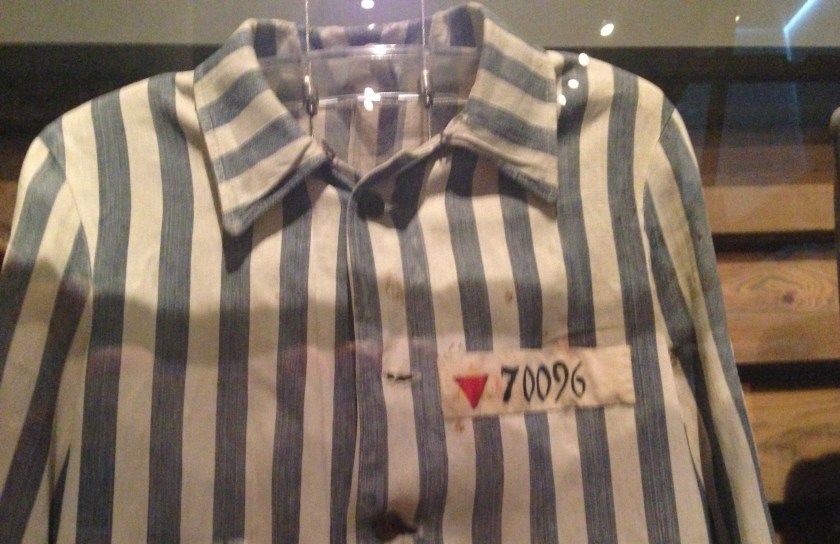

This afternoon I visited Yad Vashem, Jerusalem’s Holocaust Museum. Visiting it is a profound experience. The basic story, I knew. What I found most moving were the images of the people who were killed and the many filmed interviews with survivors.

This afternoon I visited Yad Vashem, Jerusalem’s Holocaust Museum. Visiting it is a profound experience. The basic story, I knew. What I found most moving were the images of the people who were killed and the many filmed interviews with survivors.

The whole museum began to feel like an exercise in national myth making: Israel exists because of the Holocaust. I thought perhaps I was being too critical and reading too much into things.

The whole museum began to feel like an exercise in national myth making: Israel exists because of the Holocaust. I thought perhaps I was being too critical and reading too much into things.

Sitting on the public beach in Aqaba. It’s evening. The sun will set soon, behind Egypt and Israel, which are nearby and visible around the corner, on the other side of the Red Sea. On this side, less than 20 kilometers south, is the Saudi border.

Sitting on the public beach in Aqaba. It’s evening. The sun will set soon, behind Egypt and Israel, which are nearby and visible around the corner, on the other side of the Red Sea. On this side, less than 20 kilometers south, is the Saudi border. Suddenly, the loudspeaker from the mosque on the other side of the street sings out the call to prayer. A group of four female tourists arrive, Japanese perhaps. They stand in front of me getting close to the local families, taking pictures of the families and then selfies with the families in the background. There is a warm dry breeze off the sea.

Suddenly, the loudspeaker from the mosque on the other side of the street sings out the call to prayer. A group of four female tourists arrive, Japanese perhaps. They stand in front of me getting close to the local families, taking pictures of the families and then selfies with the families in the background. There is a warm dry breeze off the sea. So often in our lives, in my life, things run in a familiar groove. The people that I interact with most days at work or home or my cohousing community are familiar. I live in the San Francisco Bay Area, in a region of incredible beauty, cultural diversity and artistic wonder. Amidst the raft of daily chores and work duties, the sense of wonder usually gets lost.

So often in our lives, in my life, things run in a familiar groove. The people that I interact with most days at work or home or my cohousing community are familiar. I live in the San Francisco Bay Area, in a region of incredible beauty, cultural diversity and artistic wonder. Amidst the raft of daily chores and work duties, the sense of wonder usually gets lost. Tomorrow is May 1. I catch a bus back to Amman and then onto Madaba to visit Kings Academy. I am not going on to Egypt or Saudi Arabia. I am turning back.

Tomorrow is May 1. I catch a bus back to Amman and then onto Madaba to visit Kings Academy. I am not going on to Egypt or Saudi Arabia. I am turning back. The sound of the water lapping the shore becomes audible as people drift away and back to their daily lives. Then a new family arrives to set up their blanket in the sand. Another little wave crashes into the land and another and another…

The sound of the water lapping the shore becomes audible as people drift away and back to their daily lives. Then a new family arrives to set up their blanket in the sand. Another little wave crashes into the land and another and another… It’s my second and final day in Wadi Rum. No rain today. There was a beautiful sunset over the desert. Tonight, the mountains and sand glow under a full moon. I woke up yesterday in Wadi Musa, the town outside Petra. Wadi Musa translates as ‘Valley of Moses’ and supposedly this is the place where Moses struck a rock to bring out water. Me and a bus full of 20 somethings with their backpacks took the two-hour ride down to Wadi Rum. Khaled, who runs the camp I was staying in–there are apparently 60 Bedouin camps in Wadi Rum–was waiting in the village.

It’s my second and final day in Wadi Rum. No rain today. There was a beautiful sunset over the desert. Tonight, the mountains and sand glow under a full moon. I woke up yesterday in Wadi Musa, the town outside Petra. Wadi Musa translates as ‘Valley of Moses’ and supposedly this is the place where Moses struck a rock to bring out water. Me and a bus full of 20 somethings with their backpacks took the two-hour ride down to Wadi Rum. Khaled, who runs the camp I was staying in–there are apparently 60 Bedouin camps in Wadi Rum–was waiting in the village. Coming down, a boy driving a truck said Khaled’s name and pointed to the back for me. This was Omar, Khaled’s 17-year-old nephew. The back had two metal benches and a tarp over the top. Off we went across the sand. We arrived at a spot with a dozen similar-looking trucks and lots of people. He said, “Lawrence’s Spring” and pointed up the mountain. And so it went.

Coming down, a boy driving a truck said Khaled’s name and pointed to the back for me. This was Omar, Khaled’s 17-year-old nephew. The back had two metal benches and a tarp over the top. Off we went across the sand. We arrived at a spot with a dozen similar-looking trucks and lots of people. He said, “Lawrence’s Spring” and pointed up the mountain. And so it went. Omar doesn’t speak much English but did make a delicious lunch. Gathering wood from small dead bushes, he built a fire to cook up some tomato and bean stew. Add baba ghanoush, Greek salad, pita bread, fruit and you have a desert feast.

Omar doesn’t speak much English but did make a delicious lunch. Gathering wood from small dead bushes, he built a fire to cook up some tomato and bean stew. Add baba ghanoush, Greek salad, pita bread, fruit and you have a desert feast. After a very cold night in the dessert, the skies were completely clear this morning. Today my guide was Eid Sabah, Omar’s father. We headed off to a remote part of Wadi Rum that isn’t on the standard tourist route. I went for a three-hour walk on the desert floor. Eid Sabah would point me in a direction and then drive past me in the car 20 minutes later. When I caught up with him, he’d point again, and we’d repeat the process.

After a very cold night in the dessert, the skies were completely clear this morning. Today my guide was Eid Sabah, Omar’s father. We headed off to a remote part of Wadi Rum that isn’t on the standard tourist route. I went for a three-hour walk on the desert floor. Eid Sabah would point me in a direction and then drive past me in the car 20 minutes later. When I caught up with him, he’d point again, and we’d repeat the process. It was sunny, but not hot. There was something very calming about walking along the desert sand, through the beautiful rock formations. I was reminded that humans are designed for walking long distances. I felt I could have walked for days.

It was sunny, but not hot. There was something very calming about walking along the desert sand, through the beautiful rock formations. I was reminded that humans are designed for walking long distances. I felt I could have walked for days. For my final hike, he took me to a spring that was about an hour walk from camp. In the side of the mountain, down five stone steps in a cave, was a pool. I sat there looking down at the cool water and out into the bright light of the valley.

For my final hike, he took me to a spring that was about an hour walk from camp. In the side of the mountain, down five stone steps in a cave, was a pool. I sat there looking down at the cool water and out into the bright light of the valley. Arriving back at camp, I grabbed the pot of tea and a couple of glasses. There was one woman sitting on the ledge above camp reading. We instantly took to chatting and talked for most of the next four hours. What a delight.

Arriving back at camp, I grabbed the pot of tea and a couple of glasses. There was one woman sitting on the ledge above camp reading. We instantly took to chatting and talked for most of the next four hours. What a delight. After saying good night, we walked out into the light of the full moon. I headed off into the desert sand. I told Tamara that I could happily travel for a year. Take the ferry from Aqaba to Egypt. It has been such a treat to be outside of the details of work, to be connecting with interesting people from around the world, to be soaking in the beauty of amazing places on the planet.

After saying good night, we walked out into the light of the full moon. I headed off into the desert sand. I told Tamara that I could happily travel for a year. Take the ferry from Aqaba to Egypt. It has been such a treat to be outside of the details of work, to be connecting with interesting people from around the world, to be soaking in the beauty of amazing places on the planet.

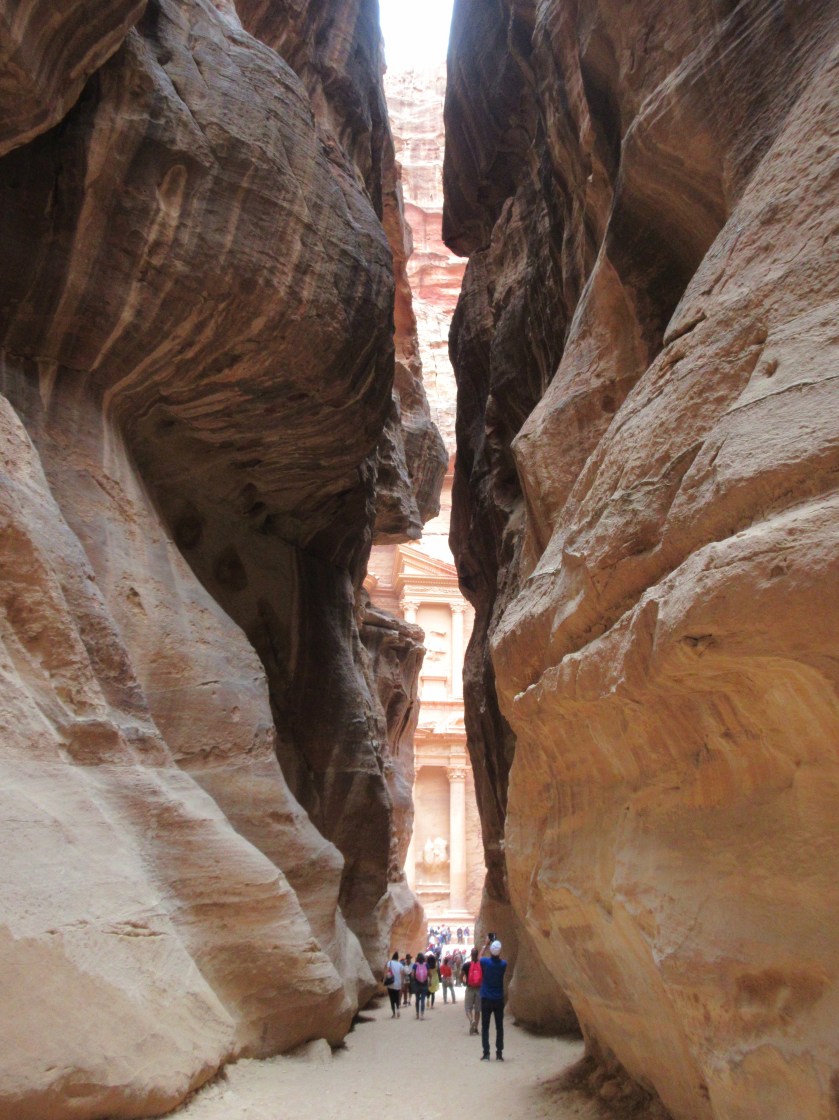

I accepted a ‘free’ horse ride for the first 400 meters from the parking lot to the entrance to the Siq. This was probably a mistake, as I then had to listen to his sales pitch for a longer ride that I would pay for. He wouldn’t take no for an answer. Perhaps he thought I was a tough bargainer. His price kept dropping each time I walked away.

I accepted a ‘free’ horse ride for the first 400 meters from the parking lot to the entrance to the Siq. This was probably a mistake, as I then had to listen to his sales pitch for a longer ride that I would pay for. He wouldn’t take no for an answer. Perhaps he thought I was a tough bargainer. His price kept dropping each time I walked away. The Siq is a long narrow canyon. The first glimpse of the Treasury as you walk down the Siq is still thrilling the second time.

The Siq is a long narrow canyon. The first glimpse of the Treasury as you walk down the Siq is still thrilling the second time. On my first day in Petra I hiked to the High Place of Sacrifice. There is a ceremonial route up with various tombs and sites along the way. At the top is a sacrificial altar, with a basin for collecting the animals’ blood and a blood drainage system off the basin. I had read about such places—and maybe seen them depicted in movies—but I don’t think I’d ever been at one before. It reminded me a little of Machu Picture, a stunning place of ritual high in the mountains.

On my first day in Petra I hiked to the High Place of Sacrifice. There is a ceremonial route up with various tombs and sites along the way. At the top is a sacrificial altar, with a basin for collecting the animals’ blood and a blood drainage system off the basin. I had read about such places—and maybe seen them depicted in movies—but I don’t think I’d ever been at one before. It reminded me a little of Machu Picture, a stunning place of ritual high in the mountains. Part of what’s amazing about Petra is that you can pretty much go anywhere—hiking in any direction, scrambling over rocks. Or, as I saw two tourists do, you could use the Place of High Sacrifice altar as your picnic table.

Part of what’s amazing about Petra is that you can pretty much go anywhere—hiking in any direction, scrambling over rocks. Or, as I saw two tourists do, you could use the Place of High Sacrifice altar as your picnic table. The people running Petra started bringing little pick-up trucks—yes, just like bakkies—down the Siq. As many people as possible clambered into the back and the truck drove up the stream flowing down the Siq to get them out. There were 3-4 trucks ferrying people out. After the second round left, they announced that the threat of flooding was past and that hiking out the Siq was allowed. I knew that my feet would be soaked by the time I was done, but how often do you get to hike out of Petra when the Siq has turned into a creek? How fun!

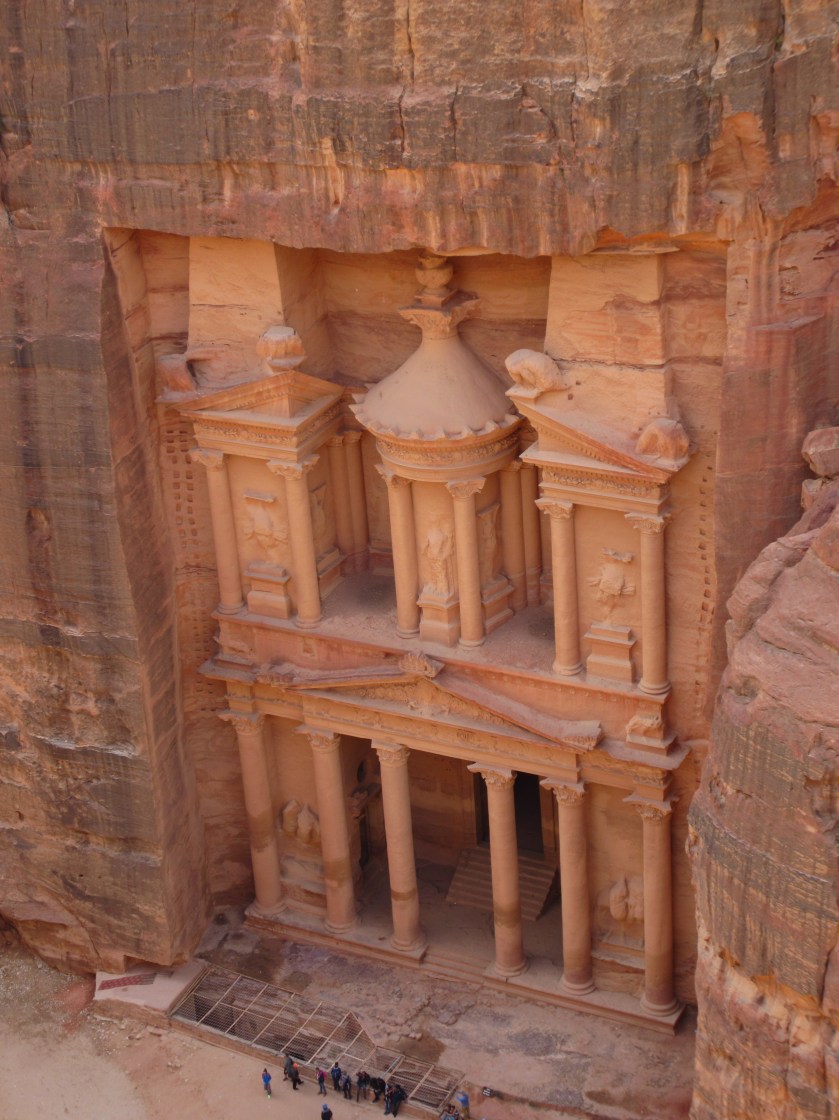

The people running Petra started bringing little pick-up trucks—yes, just like bakkies—down the Siq. As many people as possible clambered into the back and the truck drove up the stream flowing down the Siq to get them out. There were 3-4 trucks ferrying people out. After the second round left, they announced that the threat of flooding was past and that hiking out the Siq was allowed. I knew that my feet would be soaked by the time I was done, but how often do you get to hike out of Petra when the Siq has turned into a creek? How fun! The next day I did another climb, this time to get a view looking down at the Treasury. It was remarkable looking at how the Nabataean people had cut the stairway into the mountain. I tried to imagine what their lives might be like.

The next day I did another climb, this time to get a view looking down at the Treasury. It was remarkable looking at how the Nabataean people had cut the stairway into the mountain. I tried to imagine what their lives might be like. I saw a keffiyeh head scarf in earth and terra cotta, the colors of my school–think of an ancient Athenian vase–and stopped to buy it. The Bedouin who used to live in Petra, now are allowed to sell horse rides and trinkets at the site. As you walk through the ruins you are regularly exhorted to stop and look at someone’s wares. The proprieter of this stall was reclining as he waited for a customer. Nomadic people carrying tents and carpets, chairs are not a big part of the local culture. For example, the room I’m in here at this camp in Wadi Rum, which is the main eating space, has no chairs. Carpets on the floors and walls. Pads to sit on and lean against. Tables with short legs, ½ meter off the ground. But no chairs. I thought of Passover and the question about reclining.

I saw a keffiyeh head scarf in earth and terra cotta, the colors of my school–think of an ancient Athenian vase–and stopped to buy it. The Bedouin who used to live in Petra, now are allowed to sell horse rides and trinkets at the site. As you walk through the ruins you are regularly exhorted to stop and look at someone’s wares. The proprieter of this stall was reclining as he waited for a customer. Nomadic people carrying tents and carpets, chairs are not a big part of the local culture. For example, the room I’m in here at this camp in Wadi Rum, which is the main eating space, has no chairs. Carpets on the floors and walls. Pads to sit on and lean against. Tables with short legs, ½ meter off the ground. But no chairs. I thought of Passover and the question about reclining.

South Africa is a beautiful place and South Africans are beautiful people. Almost everyone I met has been gracious and hospitable, more so than in the USA where people’s work-related busyness often gets in the way. The diversity of cultures and languages is stunning and I didn’t even scratch the surface. This is an gorgeous place and South Africans, both black and white, love the land.

South Africa is a beautiful place and South Africans are beautiful people. Almost everyone I met has been gracious and hospitable, more so than in the USA where people’s work-related busyness often gets in the way. The diversity of cultures and languages is stunning and I didn’t even scratch the surface. This is an gorgeous place and South Africans, both black and white, love the land. The country’s unique history is well-known, but it is fascinating being here and seeing its effects. Most stunning to me was how apartheid era housing laws still seem to provide the basic blueprint for where most people reside.

The country’s unique history is well-known, but it is fascinating being here and seeing its effects. Most stunning to me was how apartheid era housing laws still seem to provide the basic blueprint for where most people reside. Here is a final—hopeful—story. Yesterday I visited the Solms-Delta vineyard in Franschhoek. Ella Solms came on exchange to the Athenian School two years ago and hosted a student from my school. A few years ago a trust was created and 45% of the vineyard is owned by the workers at the vineyard.

Here is a final—hopeful—story. Yesterday I visited the Solms-Delta vineyard in Franschhoek. Ella Solms came on exchange to the Athenian School two years ago and hosted a student from my school. A few years ago a trust was created and 45% of the vineyard is owned by the workers at the vineyard.