In the bar/lounge/common area of Abraham’s Hostel in Jerusalem. The hostel says Abraham was the ‘first backpacker.’ This is my fourth evening here and this floor has always been packed with people in the evening. Live music the last two nights.

What a unique city with a fascinating history. Just the names get this Catholic school boy all excited. Jerusalem. Garden of Gethsemane. Mount of Olives. Herod’s Gate. Tower of David.

I traveled here from Jordan on a Friday. The border closes at 1:00 on Friday afternoons because both Jews and Muslims start their religious celebrations later on Friday. I was at the border before 9:00 am in case something went wrong.

The bridge across the Jordan River is called the King Hussein Bridge. It’s also named the Allenby Bridge. Take your pick. King Hussein was a Muslim monarch of Jordan. General Allenby was the British commander who took Jerusalem in World War I and ended Muslim rule of the city for the first time since the Crusades. Before you’ve even arrived in Jerusalem you learn a central fact about this area: there seem to always be two completely different perspectives and stories. Competing all the way down to having different names. As if you’re not talking about the same thing.

Surprisingly, the Jordanian side of the border crossing was more challenging for me than the Israeli. There were no signs or written explanations of the process and where English speakers seemed to be everywhere in Jordan, suddenly they disappeared at the border. The basic process is you go to the Jordan exit terminal, take a shuttle bus five kilometers to the Israeli side, and go through immigration and customs to enter Israel. I got through the whole process in two hours. I talked to other people who took six. I was afraid the Israelis would ask lots of questions, but they asked almost none.

Once through, I took a bus to Jerusalem. There were a number of Arabs on my bus. Most of them got off at bus stops before we reached Damascus Gate. I arrived at Old City of Jerusalem to learn no cab would take me to my hostel. Turns out there was a bike race in Jerusalem that day and the road was blocked. With the help of Google Maps and after a 30-minute uphill walk, I arrived at Abraham’s

I spent the next two days wandering Jerusalem. Waling through the narrow streets of the Old City, hiking the ramparts, visiting the Church of the Holy Sepulcher and Mount of Olives. Most of my time was spent in the Old City. The Christian pilgrims were very visible, but it was clear that the residents were mostly Jewish or Muslim.

I spent the next two days wandering Jerusalem. Waling through the narrow streets of the Old City, hiking the ramparts, visiting the Church of the Holy Sepulcher and Mount of Olives. Most of my time was spent in the Old City. The Christian pilgrims were very visible, but it was clear that the residents were mostly Jewish or Muslim.

It is great to be in a place where people are so proudly and visibly Jewish. Many men wear distinctive Jewish head wear. There is the simple charmulke, which comes in many colors. There is the black top hat, sometimes looking like an undersized black sombrero and other times with a hint of Indiana Jones. And most outrageous of all is the shtreimel, a huge Jewish fur hat! And yes, many men here wear the shtreimel.

Jewish women get into the act too. Married orthodox women are supposed to cover their hair. Wearing a wig fulfills this requirement, so wearing wigs is big here among Jewish women.

Jewish women get into the act too. Married orthodox women are supposed to cover their hair. Wearing a wig fulfills this requirement, so wearing wigs is big here among Jewish women.

I enjoyed watching a Jewish family play tag or Jewish boys do hip hop dancing on a sidewalk, seeing Jewish men ride their children on a bike or Jewish women chat with each other. I saw Jewish men sitting around reading the Bible—or even reading while they walked.

I enjoyed watching a Jewish family play tag or Jewish boys do hip hop dancing on a sidewalk, seeing Jewish men ride their children on a bike or Jewish women chat with each other. I saw Jewish men sitting around reading the Bible—or even reading while they walked.

Another visible Jewish presence is the police and Israeli Defense Forces. I saw over 50 members of the Israeli police or military on patrol just today. When on patrol in the Old City they often travel in pairs. There are many women in the security forces and these pairs are often a man and a woman. They sometimes looked like a young couple.

The soldiers remind me of high school students. Most of them are just a year or two older than my students. Looking at the young soldiers, I found myself thinking that they were on some experiential education program. And perhaps they are. I wonder what they learn in three years of mandatory military service, often patrolling Muslim neighborhoods.

In my wanderings, the security forces seem to be primarily in the Muslim section of the city, which makes them feel a bit like an occupying army. There are two main gates to the Old City that people use: Damascus and Jaffa. Damascus is the main gate that Muslims use. It has three Israeli security stations at the gate. Jewish Israelis would generally not use Damascus Gate and would use Jaffa, the next gate over around the corner. No visible security presence there.

In my wanderings, the security forces seem to be primarily in the Muslim section of the city, which makes them feel a bit like an occupying army. There are two main gates to the Old City that people use: Damascus and Jaffa. Damascus is the main gate that Muslims use. It has three Israeli security stations at the gate. Jewish Israelis would generally not use Damascus Gate and would use Jaffa, the next gate over around the corner. No visible security presence there.

This morning I got up early and headed down to the Western Wall in hopes of getting to Al-Aqsa (also known as the Temple Mount). It is only open to non-Muslims a few hours a day a few days a week. There is a ramp that goes up over the women’s area at the Western Wall to a gate into Al Aqsa. I learned from a sign on the inside that this is the Moroccan Gate. There was a North African Muslim community adjacent to Al-Aqsa at this gate. After Israel captured the Old City in the 1967 war and before the fighting had even ended (which is fast, since it was a six-day war), the 600 residents of the neighborhood were given two hours to get out and all their homes were destroyed. This is what created the large open plaza in front of the Western Wall, the destruction of a Muslim neighborhood.

As I walked up the ramp, ahead of me I heard clapping and singing. A group of Jewish Israelis was going to visit the Al-Aqsa. Jews are not allowed to pray on the Mount and this group’s visit was a provocation. Several members of the Israeli Defense Forces led the group to keep them safe. The group’s members were not boisterous once they were actually inside. They slowly circled the Dome of the Rock and didn’t even go close to that shrine.

I hung out at Al-Aqsa for several hours. I walked around the Dome of the Rock three times, enjoying its architecture and glittering gold top. Most Muslim streets in the Old City lead to Al-Aqsa. There are eight gates to Al-Aqsa with guards at each. Muslims are allowed in, but others are turned away. Just the day before I had stood on the other side of the Cotton Merchants gate unable to cross though.

I hung out at Al-Aqsa for several hours. I walked around the Dome of the Rock three times, enjoying its architecture and glittering gold top. Most Muslim streets in the Old City lead to Al-Aqsa. There are eight gates to Al-Aqsa with guards at each. Muslims are allowed in, but others are turned away. Just the day before I had stood on the other side of the Cotton Merchants gate unable to cross though.

There were not many people at Al-Aqsa this day and it felt like a big park. And almost nothing else inside the Old City even felt like a little park. As I wandered, some Muslims came in to relax, chat with friends, enjoying the setting—and perhaps being in a Muslim-controlled space. I sat in the same general area and hung out. One girl brought me a sweet to share.

I heard ringing bells from Christian churches from across the city. In my mind, church bells have had a familiar soothing feel. In contrast, hearing the Muslim call to prayer seemed exotic and somehow intrusive. Sitting in Al Aqsa, I heard things differently. Christian church bells are just another form of call to prayer—and they can sound intrusive too.

Archeology is big here in Jerusalem and not just for scholars. You can take a tour of the ruins of the City of David, which is highly rated on TripAdvisor. There’s a separate tour of the tunnels under the Western Wall. The Israel Museum has a huge archeological exhibit tracing the history of Jerusalem through the ages. There is an unstated political message to all these tours—Jews have a long deep connection to this place. It largely ended in 70 CE when the Romans defeated the Jews and destroyed the Second Temple and the city of Jerusalem.

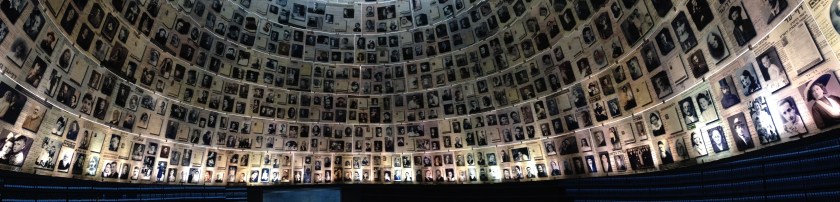

This afternoon I visited Yad Vashem, Jerusalem’s Holocaust Museum. Visiting it is a profound experience. The basic story, I knew. What I found most moving were the images of the people who were killed and the many filmed interviews with survivors.

This afternoon I visited Yad Vashem, Jerusalem’s Holocaust Museum. Visiting it is a profound experience. The basic story, I knew. What I found most moving were the images of the people who were killed and the many filmed interviews with survivors.

I went online to Yad Vashem’s database at the end. I have family members who were killed in the Holocaust in Pinsk. I looked up in the database for ‘Friedman’ and ‘Pinsk’ and got 776 matches, with 13 spelling the last name the same way as my family. Over 128,733 Jews were murdered by the Nazis in Pinsk alone.

While there were a few references to the other groups targeted by the Nazis, I was surprised how little attention they got. From what I saw at the museum, you’d have no idea that 5-6 million non-Jewish people were murdered by the Nazis.

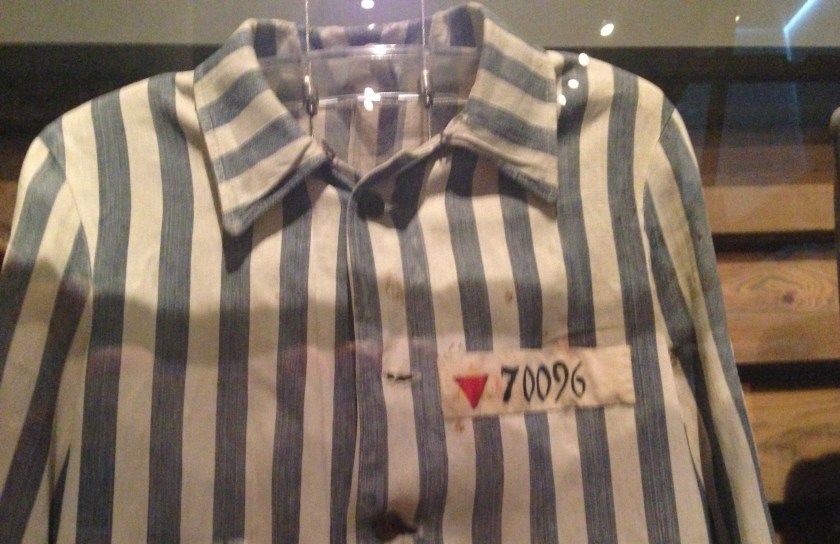

When I went to the Neuengamme Concentration Camp outside Hamburg they had a chart documenting the different symbols that people in the camps had to wear (e.g. yellow stars for Jews, pink triangles for homosexuals, etc.). I could not find this information at Yad Vashem. The museum has a display of concentration camp uniforms. It includes a uniform with a red triangle, but its significance was not explained. (A red triangle meant you were a political prisoner.)

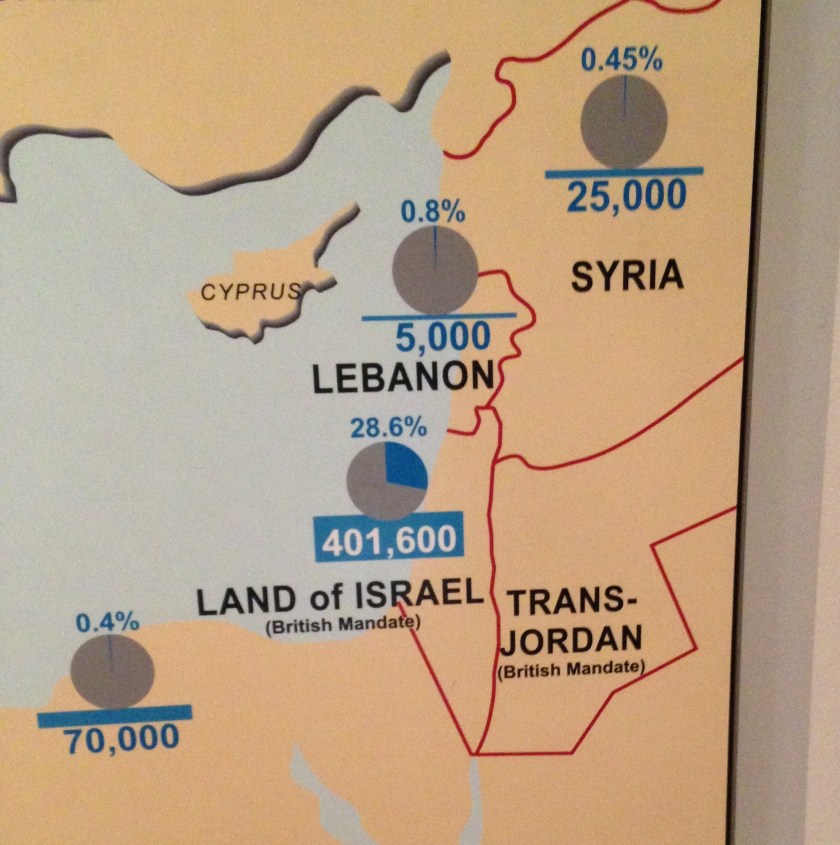

The other thing that struck me at Yad Vashem was that on the maps and placards, Palestine—which is the name that was used at the time—was always referred to as the ‘Land of Israel.’ And there’s no green line or West Bank in these maps, but all of Palestine was listed as ‘Land of Israel.’ This seemed a little presumptuous, since Israel the state didn’t exist until 1948. Britain’s refusal to allow Jewish immigration to Palestine post-WWII seemed almost nonsensical; how could you prevent Jews from coming to the ‘land of Israel?’

The holocaust museum building is a long upside-down concrete V, with a little light coming in from the top and a string of galleries on alternating sides. The ends are open and so as you finish, you walk out towards the light. You leave the building to find yourself on a balcony overlooking a beautiful valley. It’s as if this is what you get for the Holocaust, this beautiful land.

The whole museum began to feel like an exercise in national myth making: Israel exists because of the Holocaust. I thought perhaps I was being too critical and reading too much into things.

The whole museum began to feel like an exercise in national myth making: Israel exists because of the Holocaust. I thought perhaps I was being too critical and reading too much into things.

As I walked back towards the train station, I came upon a map of the grounds around the museum. There were 30 different places. Some are memorials to Jewish soldiers fighting in different armies in World War II. Some are monuments to Israeli soldiers that died in the 1967 war or the Yom Kippur war. Then I noticed that one of the sites nearby is the grave of Theodor Herzl. Theodor Herzl is the father of modern Zionism. And then I remembered the name of the tram stop: Mount Herzl.

I wasn’t reading too much into it at all. They built Yad Vashem on Mount Herzl and near the grave of the founder of Zionism. The museum was designed to convey the message that the Holocaust proves that Zionism is right.

Ironically, an interesting neighborhood that I had read was worth a visit was nearby: Ein Karem. “Far too many people leave Jerusalem without even a glimpse of Ein Karem, this picturesque neighborhood with terraced hills and churches of yore.” (Jerusalem Walking Tours website). I walked there after visiting Yad Vashem. I hiked down a long valley to the cute neighborhood. It has many old Arab houses, some sprouting Israeli flags. In 1945, Ein Karem had a population of 2,510 Muslims, 670 Christians and, apparently, zero Jews. In other words, the view from the museum porch at Yad Vashem is of a largely Muslim village that has become a Jewish suburb of Jerusalem.

Jews need to be able to live in peace and security and be able to practice their religion. But there’s one problem with Zionism: there were already people living on this land, people who aren’t Jewish, and they’re still here.

I took a political tour of Jerusalem that focused on the conflict between Jews and Muslims. The guide said one thing that I found very interesting. “Palestine and Israel are different names for the same place.” What’s your choice?