Today I returned to Colridge to work with Maggie and the folks at the soup kitchen. Maggie said that she wanted to make fry bread today–I have some skill with bread dough and I think they wanted to play to my strength–but she said they lacked the money to purchase the yeast and oil. I offered to pay and so we walked over to the nearest tuck shop. The total amount, which included a few other items, came to 160 rand—or a little over 13 US dollars.

Around 9:00 a young man came to the soup kitchen. He was introduced as their music man. He pulled a pair of big speakers out of a closet and began blasting a South African Christian song. The song was good, but it was on perpetual loop. We heard it non-stop for over six hours. After 3:00 pm, when we were well into the clean-up phase, I went and turned the music down. This meant that you could actually have a conversation. But after 20 minutes, the music was back to full blast, though gratefully a new tune had been found.

A group of older people came by the soup kitchen today. They sat in a circle under a tree by the road and chatted. It was, of course, too loud in the soup kitchen itself for them to hear each other. I was introduced around and we gave them soda and fry bread before the meal. Maggie said that one of them was the leader of the Khoi-San people.

A group of older people came by the soup kitchen today. They sat in a circle under a tree by the road and chatted. It was, of course, too loud in the soup kitchen itself for them to hear each other. I was introduced around and we gave them soda and fry bread before the meal. Maggie said that one of them was the leader of the Khoi-San people.

The soup kitchen has a large structure. They have a kitchen and professional grade portable gas burners. I cooked the fry bread on a kitchen stove inside, but all the rest of the food was cooked on a fire outside the soup kitchen next to the street. The main pot was an impressive looking kettle that the weird sisters of Macbeth would have been pleased to possess. A spoon the size of a small canoe paddle stirs the pot.

The soup kitchen has a large structure. They have a kitchen and professional grade portable gas burners. I cooked the fry bread on a kitchen stove inside, but all the rest of the food was cooked on a fire outside the soup kitchen next to the street. The main pot was an impressive looking kettle that the weird sisters of Macbeth would have been pleased to possess. A spoon the size of a small canoe paddle stirs the pot.

At meal time, they put a big tub of clean drinking water at the entrance of the soup kitchen. The soup kitchen has two tin cups at the tub. The students dip a cup in the tub, take their drink, and pass the cup on to the next student. By the end of today’s lunch, dozens, or perhaps hundreds, of students had used those two cups.

When I helped at the soup kitchen last Friday, I would estimate that we served about 100+ students. We had extra food and went to the shantytown to distribute the rest. We heard that the buses that brought the students from Huhudi, the black township, had been broken on Friday and many students were absent. The buses were running today. We did a first serving of lunch with the elders and youngest children, but wave after wave of ever older students kept coming. Lunch was bean-and-meat stew and potato salad with biscuits (cookies) for desert. We served a couple hundred students and then ran out of potato salad. Then we ran out of stew. At that point, we began making sandwiches that were beef fat and gristle on fry bread. After handing out over a hundred, we ran out of fry bread and gristle. Then we began handing out all-you-could-hold servings of the biscuits. Girls used their skirts as containers to carry as many as possible. Eventually there was nothing left to give, and Maggie shooed away the 40+ students hanging around outside the soup kitchen entrance. I regularly take students to work at meal programs in San Francisco. One thing I’d never experienced is a line of hungry folks and no food to serve.

When I helped at the soup kitchen last Friday, I would estimate that we served about 100+ students. We had extra food and went to the shantytown to distribute the rest. We heard that the buses that brought the students from Huhudi, the black township, had been broken on Friday and many students were absent. The buses were running today. We did a first serving of lunch with the elders and youngest children, but wave after wave of ever older students kept coming. Lunch was bean-and-meat stew and potato salad with biscuits (cookies) for desert. We served a couple hundred students and then ran out of potato salad. Then we ran out of stew. At that point, we began making sandwiches that were beef fat and gristle on fry bread. After handing out over a hundred, we ran out of fry bread and gristle. Then we began handing out all-you-could-hold servings of the biscuits. Girls used their skirts as containers to carry as many as possible. Eventually there was nothing left to give, and Maggie shooed away the 40+ students hanging around outside the soup kitchen entrance. I regularly take students to work at meal programs in San Francisco. One thing I’d never experienced is a line of hungry folks and no food to serve.

Maggie continued to treat me like a benefactor. She was kind and gracious, telling people how much she’d learned from me in our two days together. I was introduced to many people who came by the shelter, was invited to speak before the meal, and was welcomed and thanked by one of the elders. Like the third-grade girl who calls me ‘my husband,’ I’m afraid that I’m going to disappoint Maggie.

Maggie continued to treat me like a benefactor. She was kind and gracious, telling people how much she’d learned from me in our two days together. I was introduced to many people who came by the shelter, was invited to speak before the meal, and was welcomed and thanked by one of the elders. Like the third-grade girl who calls me ‘my husband,’ I’m afraid that I’m going to disappoint Maggie.

Maggie is 63 years old and seems to be helping everyone: children, elders, orphans, people with disabilities. She treated me like a major benefactor, making it sound like I was a big reason for the soup kitchen’s success. Maggie called the speaker of the city council and he sent someone to welcome me to Vryburg and thank me for my efforts. We

Maggie is 63 years old and seems to be helping everyone: children, elders, orphans, people with disabilities. She treated me like a major benefactor, making it sound like I was a big reason for the soup kitchen’s success. Maggie called the speaker of the city council and he sent someone to welcome me to Vryburg and thank me for my efforts. We

Two other people worked all day with Maggie running the soup kitchen. Anita is the friendly and efficient cook. The other helper is Kathy, a transgender woman or, to use Maggie’s term, a ‘man woman.’

Two other people worked all day with Maggie running the soup kitchen. Anita is the friendly and efficient cook. The other helper is Kathy, a transgender woman or, to use Maggie’s term, a ‘man woman.’ The school day ended at 1:00 and 100-200 students came by for lunch. Lunch was a stew with beans and meat, a half-sandwich with cheese, and a lollipop. There weren’t enough plates and spoons for everyone, so half the students had to wait for the first group to finish and for their dishes to be washed.

The school day ended at 1:00 and 100-200 students came by for lunch. Lunch was a stew with beans and meat, a half-sandwich with cheese, and a lollipop. There weren’t enough plates and spoons for everyone, so half the students had to wait for the first group to finish and for their dishes to be washed. After the students left, we hit the road. The remaining stew, sandwiches and fry bread were loaded into a wheelbarrow and the remaining dinner bags went into a shopping cart. Our meals on wheels program rolled up the block to the shantytown. Young children came running with a bowl and we’d give them a half scoop of stew and some bread. The adults got a Sunday dinner bag.

After the students left, we hit the road. The remaining stew, sandwiches and fry bread were loaded into a wheelbarrow and the remaining dinner bags went into a shopping cart. Our meals on wheels program rolled up the block to the shantytown. Young children came running with a bowl and we’d give them a half scoop of stew and some bread. The adults got a Sunday dinner bag. The scene really didn’t seem that different from many neighborhoods—women hanging clean clothes out to dry, children playing in the streets—but the streets were dirt and mud, the houses were one room and made of aluminum, and there were a lot of people about.

The scene really didn’t seem that different from many neighborhoods—women hanging clean clothes out to dry, children playing in the streets—but the streets were dirt and mud, the houses were one room and made of aluminum, and there were a lot of people about.

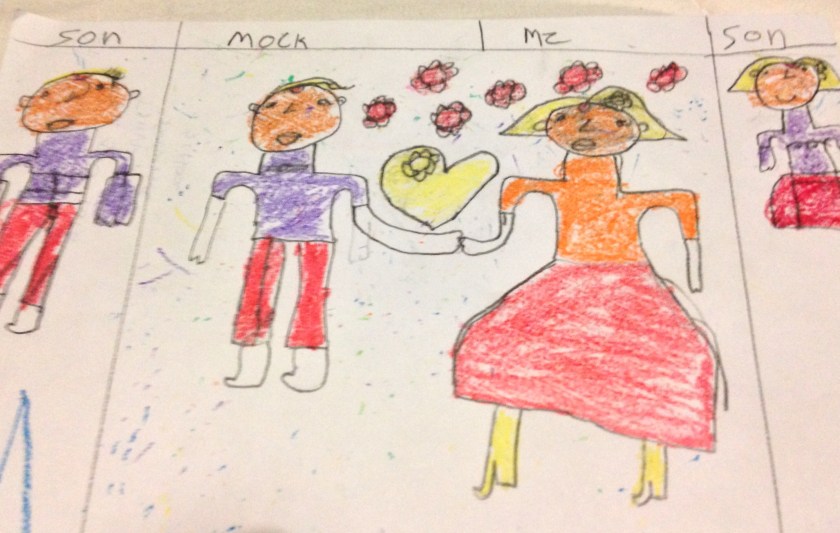

A third grade girl, Boikanyo, has repeatedly asked me to marry her. She clearly wants me all to herself. She refers to me as ‘my husband’ and makes many demands. I only sometimes do as she wants–I tell her she has to share me–so I am pretty disappointing as a husband. Perhaps this is normal husband behavior.

A third grade girl, Boikanyo, has repeatedly asked me to marry her. She clearly wants me all to herself. She refers to me as ‘my husband’ and makes many demands. I only sometimes do as she wants–I tell her she has to share me–so I am pretty disappointing as a husband. Perhaps this is normal husband behavior. Today she gave me a picture she drew. It shows the two of us, ‘Mock’ and ‘Me,’ holding hands with a big heart between us, and our two children. It seems fitting that she is by far the biggest of the two of us.

Today she gave me a picture she drew. It shows the two of us, ‘Mock’ and ‘Me,’ holding hands with a big heart between us, and our two children. It seems fitting that she is by far the biggest of the two of us.

The electricity was knocked out by two big summer storms with strong winds and rain, booming thunder, and lighting strikes overhead. The rain flooded a garage that houses two classes. We spent all of Saturday throwing away wet books and puzzles and drying out bookshelves and rugs. Last night brought another round of rain and we had to re-do the drying out today.

The electricity was knocked out by two big summer storms with strong winds and rain, booming thunder, and lighting strikes overhead. The rain flooded a garage that houses two classes. We spent all of Saturday throwing away wet books and puzzles and drying out bookshelves and rugs. Last night brought another round of rain and we had to re-do the drying out today.

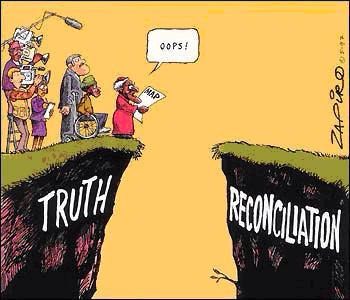

Apartheid was largely concuuent with my life. It was instituted ten years before I was born. While at Oberlin College, I attended a sit-in at a meeting of the board of trustees. We were trying to get the school to divest from companies doing business in apartheid South Africa. (There is a large sign on the building across from my hotel about divestment from Israel.) I went to hear Mandela speak at the Oakland Colleseuim when he came to the USA to thank people for their help in ending apartheid. That day he spoke about solidarity with Native Americans. Blacks in South Africa lost their land to white colonizers, akin to Native Americans in North America.

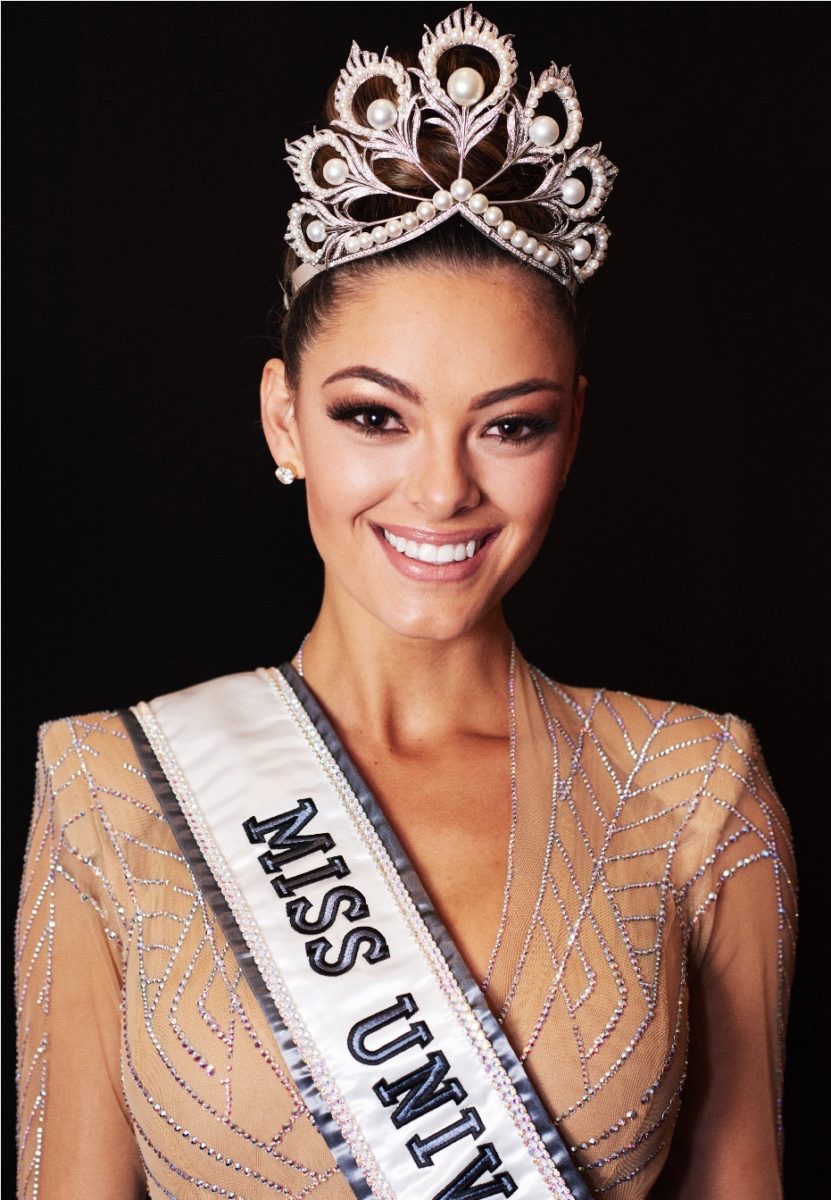

Apartheid was largely concuuent with my life. It was instituted ten years before I was born. While at Oberlin College, I attended a sit-in at a meeting of the board of trustees. We were trying to get the school to divest from companies doing business in apartheid South Africa. (There is a large sign on the building across from my hotel about divestment from Israel.) I went to hear Mandela speak at the Oakland Colleseuim when he came to the USA to thank people for their help in ending apartheid. That day he spoke about solidarity with Native Americans. Blacks in South Africa lost their land to white colonizers, akin to Native Americans in North America. Having made it through immigration and customs, I arrived at the main entrance hall of OR Tambo International Airport. There were television camera crews and a crowd gathered. It turns out that the reigning Miss Universe, Demi-Leigh Nel-Peters, is from South Africa and on a flight arriving just after mine. I accepted a ‘Welcome Home’ sign from a very thin young woman and waited. 30 members of the Soweto Gospel Choir were on hand, as well as present and past beauty queens from South Africa. Miss Teen South Africa. Miss Petite South Africa. Little Miss South Africa. The folks in the choir were all black. The tiara-wearing beauties were overwhelmingly white and none were black.

Having made it through immigration and customs, I arrived at the main entrance hall of OR Tambo International Airport. There were television camera crews and a crowd gathered. It turns out that the reigning Miss Universe, Demi-Leigh Nel-Peters, is from South Africa and on a flight arriving just after mine. I accepted a ‘Welcome Home’ sign from a very thin young woman and waited. 30 members of the Soweto Gospel Choir were on hand, as well as present and past beauty queens from South Africa. Miss Teen South Africa. Miss Petite South Africa. Little Miss South Africa. The folks in the choir were all black. The tiara-wearing beauties were overwhelmingly white and none were black. Demi-Leigh arrived to cheers and singing. She talked about how her victory was not a personal triumph, but one for all South Africans. She said that she hoped her story would inspire South African girls and boys to realize that their dreams can come true. She also mentioned that she now lives in New York City, another dream of hers. An immigrant to the United States?

Demi-Leigh arrived to cheers and singing. She talked about how her victory was not a personal triumph, but one for all South Africans. She said that she hoped her story would inspire South African girls and boys to realize that their dreams can come true. She also mentioned that she now lives in New York City, another dream of hers. An immigrant to the United States?